Editor’s Note: This article is part of our Biblical Covenants and the Conflict in the Middle East series, in which we bring together scholars with differing views on the relationship between the Biblical covenants and examine how their views affect the current conflict in the Middle East. Be sure to check out the book reviews we will post that align with each view represented.

Dispensationalists are not unanimous in their views of the appropriate biblical response of Christian churches and modern governments to the contemporary state of Israel. Specifically, we disagree on the questions (1) whether modern churchesmust privilege Jewish over Gentile missions (as an implication of Rom 1:16) and (2) whether modern nations must offer unwavering support the contemporary Jewish state (as an implication of Gen 12:3). This essay is concerned with the second of these questions. Dispensationalists of the “popular” variety tend to answer both questions positively; the dispensationalism of the academy, however, produces a more measured and mixed response.1Dan Hummel, in his helpful intellectual history of dispensationalism, identifies three major reasons for the recent loss of dispensational market share in the evangelical academy—all clustered in the late 1980s and early 1990s: (1) the Lordship debate, (2) the tension between progressive and traditional dispensationalism, and (3) the triumph of popular over scholarly dispensationalism fueled, e.g., by the “Left Behind” series (The Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2023]). It is the last of these distinctions that informs my distinction above. In this essay I speak principally for the latter.

Despite the mixed response, the spectrum of answers that dispensationalists offer to these questions is informed by shared commitments that are core concerns, viz., (1) the nature and current status of Israel’s covenants and (2) the identity of the seed of Abraham that the nations of the earth must “bless.”2I appeal here to John Feinberg (“Systems of Discontinuity,” in Continuity and Discontinuity, ed. John S. Feinberg [Downers Grove: Crossway, 1988], 67–79) and Michael Vlach (Dispensationalism: Essential Beliefs and Common Myths, rev. and upd. ed. [Los Angeles: Theological Studies Press, 2017], 30–50) and their representative listings of the “essential teachings” of dispensationalism. Both prominently include (1) the belief that Old Testament covenant promises to Israel will be fulfilled by future, national Israel, and (2) the realization that while the Bible contains multiple senses of terms like “Israel” and “seed of Abraham,” no one sense ever swallows up the others. What follows is an attempt to distill these.

What Is the Current Status of the Israel’s Covenants?

Dispensationalism, as its name suggests, operates on the notion that the biblical storyline is a history of the government of God, and that it is organized into dispensations, that is, successive administrations of the divine government. In this they diverge from the organizing premise of Covenantalism, namely, that the biblical storyline is a history of redemption that features a series of covenants in its unfolding.

Dispensationalists do not deny the existence of biblical covenants (any more than Covenantalists deny the existence of dispensations); still, our understanding of the identity and function of the biblical covenants differs substantially from that of our Reformed brothers and sisters. Firstly, dispensationalists overwhelmingly doubt the very existence of the covenant of redemption and the subsidiary covenants of works and grace. These “covenants” are neither named nor defined as such in the Bible, and for this reason offer a tenuous foundation for the biblical story. Beside this, dispensationalists find in redemption much too narrow a theme to accommodate all that God is doing, say, (1) in the window before man needed redemption, (2) through the whole company of the non-redeemed that glorifies God apart from redemption, (3) the vast throng of irredeemable angels, and so forth.3For this reason, major dispensational biblical theologies tend to prioritize kingdom rather than redemption as their controlling motif (e.g., Alva J. McClain, The Greatness of the Kingdom [Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1959], and more recently Michael J. Vlach, He Will Reign Forever[Silverton, OR: Lampion, 2017]).

By so rejecting these foundational covenant(s) of Reformed thought, dispensationalists concede a smaller number of covenants, nearly all of which (the Noahic Covenant excepted) belong uniquely to the ethnic race of people called Israelites—Paul’s brothers and sisters “according to the flesh” (so Rom 9:3–4). These covenants, as written, are irrevocable (Rom 11:29). That is to say, the covenants must be both read and fulfilled literally, or better, according to the dictates of an originalist hermeneutic: the named parties, objective terms, and mode of fulfillment—as understood by the original readers—may not evolve, may not be replaced, and may not be obfuscated via typologism.4For a favorable comparison of Constitutional originalism and biblical literalism, see my “The Originalist Hermeneutic in Biblical and Constitutional Context: Comparison and Contrast,” in Originalism in Theology and Law, ed. Mark J. Boone and Mark D. Eckel (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2024), 141–55.

With respect to the Abrahamic Covenant, then, the patently plural seed from Abram’s loins cannot be exhausted in Christ;5Galatians 3:16 does, of course, inform us that there is a singular use of seed in the OT record (though it does not identify the specific OT text[s] in view). This exception does not, however, erase the clearly plural uses of the collective noun in the OT that regard its value as being “as numerous as the stars in the sky and as the sand on the seashore” (Gen 22:17 cf. 15:5; 26:4; 32:12). the term Israel cannot lose its ethnic connotation and metamorphose, after the fact, into an ethnically diverse “people of God” (i.e., the church or the redeemed of every age); and the promised land so painstakingly defined in the OT (Gen 15:18–20, etc.) cannot reduce to a type of the new earth. The Abrahamic Covenant remains in force in all its original specificity—and clearly anticipates unqualified blessing and the eventual return of a vast throng ethnic Israelites to the promised land. Dispensationalists are resolute on these points. We note further that there are no curse clauses for Israel in this covenant nor provision for the suspension of the earlier promise of divine blessing or of the requirement of blessing by the “peoples of the earth” (Gen 12:3). The expectation of blessing is open-ended and continuing and is not dependent in any sense upon the spiritual condition of the Jewish people.

The terms of the Mosaic and Davidic Covenants, however, do anticipate the possibility of disobedience unto the suspension (but never the cancellation) of the blessings imbedded in those covenants. In short, the Israelite kingdom is susceptible to temporary dissolution—a dissolution realized during the Exile and never fully reversed. In Eugene Merrill’s words, Israel’s “function and capacity as a holy nation and priestly kingdom depend on her faithful adherence to the covenant made with Moses,” but “the election of Israel to be the people of Yahweh by promise and redemption is unconditional.”6“A Theology of the Pentateuch,” in A Biblical Theology of the Old Testament, ed. Roy B. Zuck (Moody Press, 1991), 35, emphasis added.

The New Covenant details the return of Israel to their land en masse and in faith (Jer 31:31ff; Ezek 36:24–32; Zeph 3:8ff; Rom 11:26; etc.), bringing relief to the earlier covenants. However, this covenant anticipates not contemporary but eschatological fulfillment. Irrespective of any new covenant benefits that might accrue to the Christian Church, the covenant itself does not find fulfillment until Israel enters into covenant with her Messiah (Jer 50:5; Hos 2:18–23; Zech 13:9; etc.) and receives all of the promised blessings collectively found in all of her earlier covenants, beginning with the Abrahamic.

Our brief survey of the covenants complete, we have suggested that the Abrahamic Covenant and its expectation of “blessing” remains open, and that it will be fully realized in the eschaton. But questions remain. Namely, in the meantime, (1) who exactly must bless whom and (2) what does this “blessing” look like?

Who Are Abram’s Seed and Who Are the Peoples of the Earth?

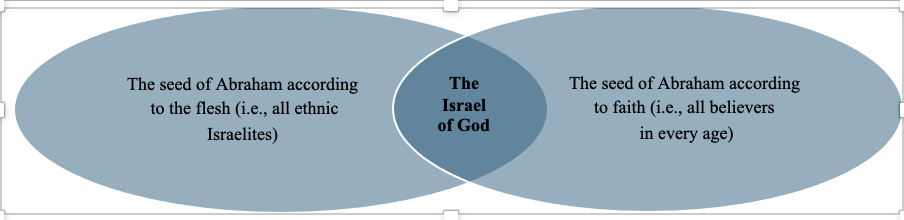

We have suggested above that the biblical seed of Abraham carries multiple senses. The majority of OT references are to (1) an expansive seed of Abraham according to the flesh—the vast multitude of Abraham’s physical descendants, descended “from his loins” (Gen 15:4–5). The NT, however, acknowledges two other uses of “seed of Abraham,” namely (2) a seed of Abraham according to faith (all believers in every age who imitate Abraham’s example of faith—Gal 3:29) and (3) a singular seed of Abraham (Jesus Christ, the descendent of Abraham who effects the promises—Gal 3:16). The first two senses overlap, and their intersection creates what Paul calls the “Israel of God” (Gal 6:16) or “true Israel” (Rom 9:6–7):

Dispensationalists argue that the terms of the Abrahamic Covenant extend specifically in context to the first of these categories: Abraham’s biological descendants—irrespective of their faith.7The covenant urges faith, of course, but the requirement to “bless” Israel is nowhere predicated on faith. As such, the peoples of the earth are not exempted from their obligation to “bless” Israel simply because some or most of Israel’s citizenry are unbelievers (a state of affairs that has been true throughout most of Israel’s history). The blessing is to be extended, without qualification, to all in every age who are “from Abraham’s loins” (Gen 12:3; cf. 15:4; Num 24:9).

More complex is the question whether the modern state of Israel is the object of blessing. Insofar as the current state of Israel is populated principally by ethnic Jews,8As of the 2022 census, 72.7% of Israeli citizens nationwide are of Jewish descent (Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, “Population Census 2022,” accessed March 12, 2025, https://www.cbs.gov.il/en/Surveys/Pages/ Population-Census.aspx). it would seem that the Abrahamic promises apply collectively to modern Israel in at least some sense. Still, following Merrill’s observation above, the legitimacy of the Israelite nation is tied directly to obedience. In the absence of such obedience, warrant for blessing the modern Israelite state is not nearly so strong as the warrant for blessing the Israelite people.

It is exegetically likely that the waning days of the Church Age will feature rudiments of the prophetic regathering of Israel. The Great Tribulation commences with a “covenant of death” between Israel and Antichrist (Isa 28:14–22 cf. Dan 9:27)—a treaty that suggests some level of existing political organization. Ezekiel 36:24–26 further affirms that Israel will gather in unbelief before being regenerated, and will convert only after they collectively “look on the one whom they have pierced” (Zech 12:10).9For a recent summary argument for this pregathering see Michael Rydelnik, How Should Christians Think about Israel (Moody Press, 2025), 43–46. This “pregathering” is not, however, carefully defined, and we cannot say emphatically that twentieth-century return of Israel to her land actually constitutes this “pregathering”—any more than the first-century nation of Israel constituted that “pregathering.” It is possible, in other words, that the present Israelite state will dissolve tomorrow without jeopardizing the dispensational system. Dispensationalism does not rise and fall with the fortunes of the contemporary Israelite state—only with the survival of the Jewish people.

As to who, specifically, should bless the Jewish people, we have the phrase, “the peoples of the earth.” In context, this designation should likely be seen not so much in personal or ecclesiastical terms, but principally as organized political units.10Perhaps the purest example of this is the streaming of the nations, first to assist Israel in her rebuilding, and perpetually to share with Israel of their wealth during the Millennial Kingdom (Isa 61–62; cf. 2:2; etc.). While individual Christians and institutional churches should no doubt extend kindness and evangelistic concern to Jews individually and collectively, the original context does not have these in view.

What Does It Mean to “Bless” Israel?

The question that stands at the heart of the issue under review and raises the greatest angst in the marketplace of ideas is the practical one: what does it look like for organized political units to “bless” Israel? I will answer this question first by defining blessing and its counterpart cursing, then by teasing out implications in the civic sphere.

Defining Blessing: A Lexical Issue

The simplest glosses for the verb to bless (Heb. barak) are to “favor” or “enrich.”11[11]HALOT, s.v. “ברך.” To bless someone is firstly to think well of them and then to seek their best interests or wellbeing. Nearly as informative to our discussion is Moses’s antonym, to curse (Heb. qalal), which speaks firstly of scorn for a person/group (to “have a low opinion of”; to “despise” or “disdain”; to regard as “insignificant” or “contemptible”), and only then to one’s actions toward them (to “neglect” or “abuse”).12HALOT, s.v. “קלל.” Note that the lexicon dedicates its first two numbered sections to the idea of contempt and only one (the last) to the idea of injury. The Greek term for blessing, eulogeō, also tilts to the idea of high regard and (quite literally) to “speaking well” of someone by invoking divine favor on them. That is not to say that there is no room for “bestowing favor; providing with benefits”;13BDAG, s.v. “εὐλογέω,” def. 3. however, all the terms under review prioritize affection over action. We are to treat ethnic Israelites firstly with courtesy and then with practical concern.

Bestowing Blessing: A Practical Issue

Before making positive suggestions about what civil “blessing” looks like, we reiterate first that this requirement to “bless” Israel does not demand the establishment or preservation of any given Israelite state in the present age. In short, to be a dispensationalist does not require one to be a Zionist.14Christian Zionism argues not only “that Israel has a corporate future in God’s plan” (which dispensationalists all hold), but also that “as a nation has a [perennial] right to land in the Middle East…and be recognized as such in the world” (Darrell Bock, “How Shall the New Christian Zionism Proceed?” in The New Christian Zionism: Fresh Perspectives on Israel and the Land [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2016], 308–10, emphasis added). The notion of “Zionism” as defined here is held by some (though not all) dispensationalists, but is not, ironically, a uniquely “dispensational” notion. The modern rise of Zionism has far more to do with English Puritanism and German Pietism, in fact, than with dispensationalism, which it predates by centuries. Zionism’s earliest impetus was postmillennial interest in regathering Israel in their land—not by supernatural means, but by the ordinary efforts of concerned churches ostensibly charged with establishing the Kingdom as faithfully described in the Old Testament (see Donald M. Lewis, A Short History of Christian Zionism [Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2021] 57–91; cf. also passim in Iain Murray, The Puritan Hope: A Study in Revival and the Interpretation of Prophecy [Carlisle, PA: Banner of Truth, 1971]; also Peter Toon, ed., Puritans, the Millennium, and the Future of Israel [Cambridge: James Clarke & Co., 1970]). This differs significantly from the dispensational expectation. Nor does “blessing” demand carte-blanche support of every Israeli policy, much less the casting of a blind eye toward her ethical failures and crimes—after all, such responses are not in Israel’s best interest. Concern for Israel as a nation or of Jews individually never negates God’s general concern for justice, righteousness, and neighborliness among humanity at large.

The positive expression of this “blessing” in the present age is unspecified, and it seems unwise to add more specificity than the Scriptures do. Still, three key points may be established: (1) “Blessing” (and not “cursing”) prohibits not only abuse, but also contempt directed toward Jewish people qua Jewish people. It anticipates instead (2) active sympathy and regard for Jewish people (both individually and collectively) and contribution to their wellbeing and flourishing. Furthermore, there seems to be an implication of (3) singular favor afforded to the “seed of Abraham” that is greater than that afforded to other ethnic groups.15One might compare the special favor one affords family members. Parents have a greater obligation for their children’s welfare than, say, that of their neighbors or of humanity generally. However, it is never right for parents to dismiss (much less endorse) their children’s acts of sin, forego their discipline, or permit them to act unjustly. I would venture that the obligation of civil societies to “bless Abraham’s seed” manifests similarly. Beyond this, however, the covenants are not specific.

Summary

Dispensationalists unanimously concur that the terms and referents of Israel’s covenants do not change and that the covenants never expire. As such, while dispensationalists concede that the current scattering/exile of Israel has rendered the modern obligation to “bless” Israel a bit murky, all agree that at least some obligation to bless Israel persists in the present day. Agreement breaks down, however, in the details: precisely who is to bless and be blessed, and precisely what constitutes “blessing.” The foregoing has offered a faithful attempt to answer these questions according to the standard opinions of the dispensational academy. It concludes that dispensationalists are not (necessarily) Zionists and certainly do not advocate for unqualified support of the modern state of Israel. Still, if the Abrahamic Covenant retains ongoing significance (and we contend that it does), it entails that the “peoples” of the earth bear a continuing obligation to regard the ethnic “seed of Abraham” with sympathy and to seek their wellbeing within the bounds of justice and ethical propriety.

Author

-

Dr. Snoeberger has been Professor of Systematic Theology at Detroit Baptist Theological Seminary (Allen Park, MI) since 2008. He is an active member of the Evangelical Theological Society and has published numerous materials on dispensational themes, including the “Traditional Dispensationalist” perspective in Covenantal and Dispensational Theologies: Four Views (IVP, 2022). He has a forthcoming volume on dispensationalism in Kregel’s "40 Questions” series (expected publication in early 2027).

View all posts