This essay endeavors to bring much needed light to a conversation that has a surplus of heat. I have attempted, for the most part, to stay away from public disputation with Dr. Owen Strachan for a number of reasons. One reason is simply that the prospect of it saddens me. Strachan was one of my professors at Midwestern Seminary, both at the graduate and doctoral level. I am genuinely grateful for the time and energy he poured into teaching me. Not only did I sit under his tutelage in the classroom setting, I served for over a year as his teaching fellow and helped with research for a number of his projects. I also worked closely with him on event planning and communication when he was the director of Midwestern’s Doctoral Residency program. Some of the most helpful advice I received in seminary came in his dimly-lit office, under the watchful gaze of those paintings of Jonathan Edwards and Winston Churchill and William F. Buckley that lined his walls. It was there that he introduced me to Roger Scruton, a debt I don’t think I’ll ever be able to repay. Which is all to say, my love for Dr. Strachan runs deep, having been developed through a number of relational ties. So, the thought of a public dispute with Strachan on any level is altogether unappealing.

Additionally, I have not felt the need to enter into any of the dustups he’s been involved with because they frankly have not seemed like they were my business. For the most part, I have contented myself to address theological positions instead of persons. Granted, I have not been private about my criticisms of EFS/ERAS (which is not a critique of Strachan per se, as much as it is a critique of the position to which he holds), but even then, I have tried to be pretty restrained, since that topic is saturated with voices as is. In sum, I have had every motivation to stay out of Strachan’s theological controversies.

So, why this post? Simply put, Strachan’s recent criticisms of Classical Theism (and in particular, his recent Antithesis Podcast episode on Thomas Aquinas) are beginning to implicate me more directly by virtue of the theological positions I hold and commend. You could say he’s entering into my wheelhouse and I feel compelled to weigh in. In other words, Strachan has forced my hand. He has not done this intentionally, of course. Strachan never addresses me personally, and I am under no delusions that I loom so large in his mind as to impact his material. He owes me nothing when it comes to what he does and does not talk about, and he has been broad in his criticisms. This is perfectly legitimate. But because of the aforementioned relational ties that run deep, there are enough onlookers in my personal orbit of friendship and influence that are sure to encounter Strachan’s opinions. To the degree that his comments implicate me and the theological positions I articulate, and to the degree that his comments land within the overlap of our spheres of influence, it becomes increasingly important for me to say something. I don’t blame Strachan for any of this, and I don’t even mention it in order to complain. I simply write this to explain why, against all the strong inclination I feel to say nothing, I am compelled to say something.

Ok, enough dithering. Simply put, I wish to register three points of disputation regarding Strachan’s most recent Antithesis podcast episode. My first and primary objection to this episode is that it misrepresents the position he criticizes. I’m not sure if this is owing to a sincere failure to grasp where the issues lie or if it is a sort of exercise in misdirection (“pay no attention to the man behind the yellow curtain”). I hope the former is true, and for the purposes of this brief response, I’m going to give him the benefit of the doubt and assume that it is. Secondly, I will argue that Strachan inconsistently applies his approach to assessing the value of historical figures. And thirdly, I will argue that he muddies the water by confusing key terms. Let me address each of these points in turn.

Misrepresentation

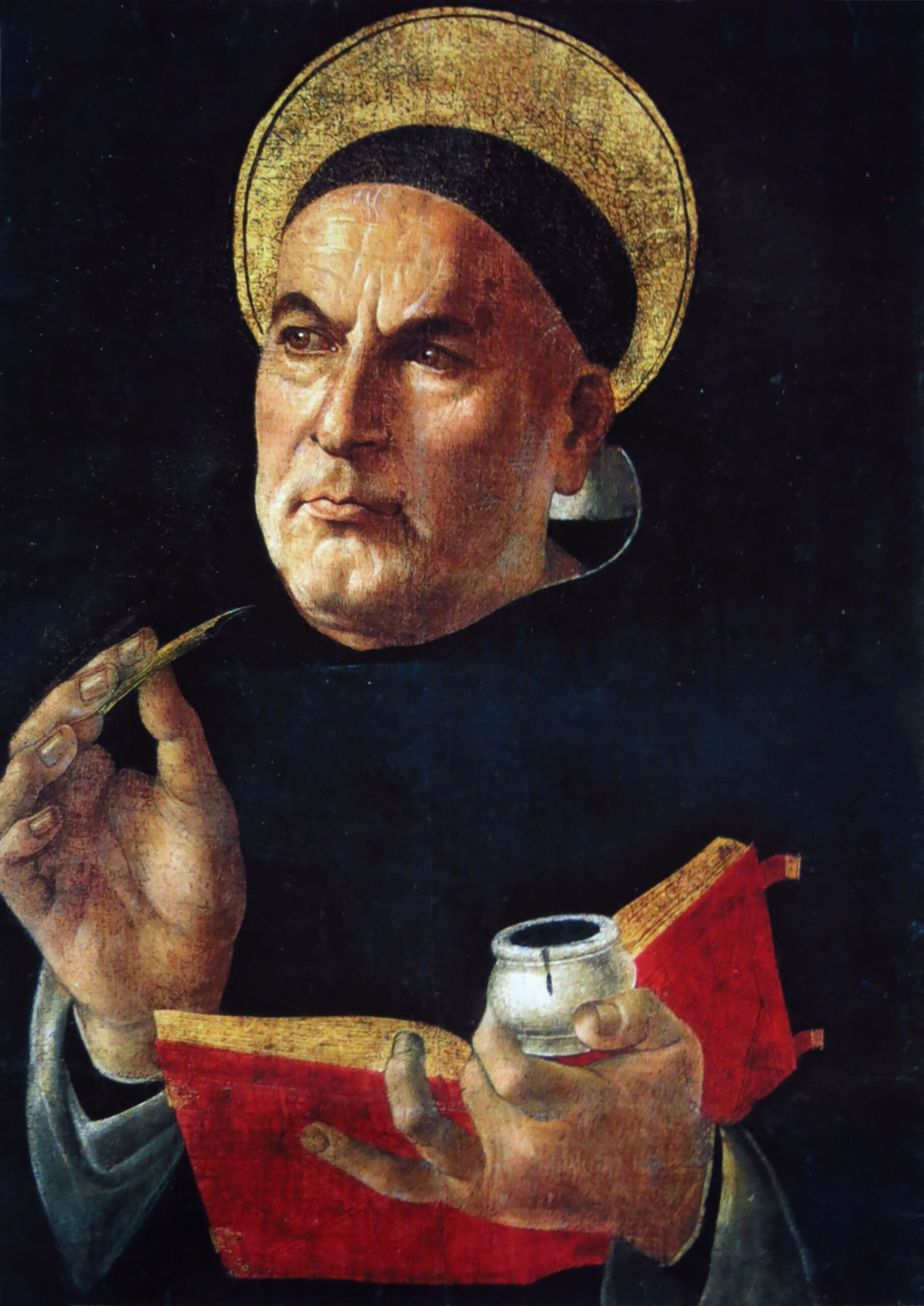

The position Strachan criticizes in this podcast episode can rightly be described as Classical Theism. This is the “camp” with which he takes issue. The practice that falls under fire is what I would describe simply as the Classical Theist variety of “theological retrieval”—in this case, the retrieval of Thomas Aquinas on certain dogmatic topics—but what Strachan calls a “protestant glow-up.” Strachan begins his program by describing the figures he takes issue with: contemporary protestants who commend Aquinas as a fruitful pedagogue. This would certainly include myself and other self-designated “Classical Theists” (to say nothing of those who are not Classical Theists, and who still speak approvingly of Aquinas). But his description of our commendation is quite inaccurate; he sets up a very tall straw man that he subsequently topples over. Strachan says:

That’s what people are saying today. People are saying, “Yes, put him [Aquinas] at the top of the list. Put him in your pantheon. Devote yourself to Aquinas. You’ve heard the wrong idea about him; he’s been mischaracterized. He’s basically a protestant.” Or, if they don’t use that language, “He’s one that protestants can learn a tremendous amount from.”

There is quite the range of statements strung together here, and some of them are true enough. We would say that many have heard the wrong idea about Aquinas. We would say that he’s been mischaracterized and that protestants can learn a lot from him. But these basic claims are thrown in with outlandish supposed claims like, “he’s basically a protestant,” and “put him in your pantheon.” To state the obvious, there is a world of difference between “Aquinas is basically a protestant,” and “protestants can learn a lot from Aquinas.” I have seen plenty of Protestants say the latter, but none who have said the former. On one level, I can understand why Strachan might prefer that we come out and say something like this. It is convenient, rhetorically speaking, to lampoon a Protestant who says, “Aquinas is basically a protestant;” the only problem is, none of us are actually saying that.

This kind of mischaracterization carries over into the rest of the podcast as well. For example, Strachan objects to seven areas of Aquinas’s thought: (1) his apophatic theology (i.e., his denial that creatures can know the essence of God), (2) his understanding of justification, (3) his treatment of the sacraments, broadly speaking, (4) his understanding of baptismal regeneration in particular, (5) his doctrine of the papacy, (6) his teaching that penance removes sin, and (7) his teaching on indulgences. Now, apart from his first objection (to which I will return below), I stand broadly with Strachan, against Aquinas, on nearly all of these matters (even while I would articulate my position differently than Strachan), and I am not unique in this respect. Virtually none of the Protestant Classical Theists who have engaged in theological retrieval commend Aquinas’s soteriology or his ecclesiology. Even a Lutheran understanding of baptism (which affirms baptismal regeneration) differs from Roman Catholic dogma on baptism. But the entire podcast is framed as providing reasons why protestants who commend Aquinas are wrong for doing so. This is confusing, however, since, so far as I am aware, none of the Protestants who commend him do so with respect to these soteriological and ecclesiological subjects.

If Protestants who speak highly of Aquinas do not mean to advocate for his soteriology or ecclesiology, what do they mean to commend? Those of us who consider ourselves Classical Theists often bring up Aquinas in the context of theological retrieval because the doctrines we are most preeminently concerned with retrieving are, among other things: theology proper, trinitarianism, Christology, and creation. We argue there is a strong continuity throughout church history on these perennial topics, and they come to us in clear and mature articulations in the work of Thomas Aquinas.

Of course, to concern ourselves with “retrieving” presupposes we believe that whatever it is we are retrieving has been lost. This, in my estimation, is where the conversation needs to take place: the Classical Theist charge that the modern era of theology—across the board, liberal and conservative alike—is marked by a radical revisionism regarding these important doctrines. We would argue that theology proper, doctrines like simplicity, immutability, and impassibility, have undergone radical revisions and/or rejections. The same is true for metaphysical realism in the doctrine of creation, eternal modes of subsistence and inseparable operations and virtually the entire historical western framework in trinitarianism, and a consistently Chalcedonian understanding of the hypostatic union in Christology. Theistic personalism, social trinitarianism, metaphysical univocism and nominalism, kenotic Christology—all of these are commonplace in Christianity today, particularly among evangelicals.

Strachan certainly has a dog in this fight, since he has not been private about his convictions on these topics. His articulations of Trinitarianism and Christology in particular are, in my estimation, revisionistic (and, we should acknowledge, he has this in common with the likes of Bruce Ware, Wayne Grudem, and John Frame). Classical Theists believe that the sentiments of Strachan and others on these topics today is a departure from the tradition. We would argue that one figure who has written fruitfully and helpfully on these doctrines, which have undergone radical revisions, is Thomas Aquinas. In saying so, we are saying no more and no less than what just about any typical figure within the Protestant Reformed tradition might say (again, until the past couple hundred years). That is the claim from Strachan’s opponents. That is the debate, as far as they are concerned. Aquinas comes in precisely here: he is not the primary point, theology is. Obviously, others are invited to debate this claim in good faith, and many prominent thinkers do. But ideally, those who engage are able to understand where Aquinas actually fits into the discussion. He is a helpful resource for many reasons, not the least being his contributions to certain theological positions that modern theologians have revised.

It is true that the early Reformers and their immediate progeny (i.e., the Reformed Orthodox and the Puritans) spoke far more about where they diverged from Aquinas than what they could learn from him. But this is simply because they had not rejected what was already in common within like we moderns have. The polemics of every age are always occasional—determined by the controversies of the time. For example, in his book, A Reformed Catholic, William Perkins analyzes Roman Catholic theology in all of the major loci that distinguished Protestants from Roman Catholics. With each of these topics, Perkins approaches his work with painstaking clarity to demonstrate where Protestants and Roman Catholics agreed, where they differed, what Rome taught, and what Protestants taught by contrast. We can learn a lot from Perkins’s winsome and nuanced approach in general, but I bring this work up not to highlight what Perkins discusses, but rather what he leaves out. In a book whose purpose is to systematically show where Protestants and Roman Catholics disagree, Perkins never addresses theology proper, trinitarianism, or the incarnation and Christ’s two natures in the hypostatic union. Why would he leave these out? Because there was no conflict between Rome and the Protestants on these matters—they stood in basic agreement. The implication is that, were they alive today, the Protestants of yesteryear would agree with Roman Catholics and disagree with many contemporary evangelicals on these matters (i.e., theology proper, trinitarianism, Christology). In fact, we need not speculate on this matter. Our Protestant forefathers (both the Magisterial Reformers and the Protestant Scholastics) appropriated Aquinas in countless ways. The literature proving this point is immense, with entire illustrious careers like that of Richard Muller dedicated thereunto. Strachan sidelines this entirely when he makes blanket statements about the supposed uniform denunciation of Aquinas by the Reformed tradition. The Reformed tradition has both denounced and appropriated Aquinas in diverse ways.

To be sure, the divisions that existed between Rome and the Reformers have not gone away, and those of us who identify within the Protestant Reformed tradition and who want to retrieve Classical Theism are not leaving those disputes behind. We are not done protesting. Figures like J.V. Fesko, Matthew Barrett, Michael Horton, and Samuel Renihan have not been silent regarding those Reformed distinctives that stand in contrast to Roman Catholicism: they do not show signs of wavering on their affirmation of the five solas (in my forthcoming volume with Christian Focus, Irresistible Beauty: Beholding Triune Glory in the Face of Jesus Christ, I labor to do the same thing: I stand firmly with the Protestant and Reformed conception of soteriology over and against Rome).

We are not getting cozy with Rome, we are merely saying the same “amen” with Aquinas that our Reformed forbearers said: “amen” on theology proper, trinitarianism, Christology, and creation. If it appears that we are getting overly ecumenical, and are blurring the lines between Rome and Geneva, it is only because modern revisionist accounts of theology have done such a number on Theology proper that the distance of resemblance between such evangelicals today and the Christianity of the great tradition is greater, in crucial ways, than the distance between the Reformers and their papist counterparts. In other words, I have no fewer differences with Roman Catholics on doctrinal matters than the Reformers did. Where I (and the Reformers) stand with many Catholic thinkers (including Aquinas) puts me at odds with contemporary evangelicals like Strachan in matters of first importance. I would argue that in this case, it is not that I and other classicists are moving toward Rome, but rather that Strachan and other theological revisionists in the modern era are moving away from the tradition. At various points in this podcast, Strachan suggests that Protestants who are praising Aquinas for any reason are somehow blurring the distinction between Protestantism and Roman Catholicism. This is untrue. We simply want to draw the line that distinguishes one from another at the right place.

Again, I grant that this insistence that the Reformed tradition stood in continuity with Aquinas and the majority of the Christian tradition on theology proper is up for debate, but this is the debate we’re interested in having, not whether Aquinas should be commended wholesale by Protestants (including his soteriology and ecclesiology). Such a debate would be boring, with Strachan and virtually every Protestant classicist taking the negative of the proposition, leaving the positive side of the table vacant. This is where I believe Strachan mischaracterizes. He seems to imagine he is arguing with classical protestants in this podcast episode, but I don’t recognize anybody in the interlocutors he imagines. By failing to accurately represent the position his opponents hold, all his attempted blows amount to shadow-boxing.

Inconsistent “All-or-nothing” Approach to Historical Retrieval

Of course, at this point, Strachan may simply object to the proposal of appropriating Aquinas’s theology proper or his Christology while rejecting his soteriology and ecclesiology. Indeed, he seems to indicate that such a proposal is a kind of failure of nerve when he attempts to call us on our bluff, so to speak. It almost comes off like a dare: if Aquinas is going to be embraced in the seminary, “he should be brought into small groups,” says Strachan, “pastors should be regularly quoting him from the pulpit. If he’s going to be embraced, let’s embrace him, let’s embrace him all the way.” This seems to imply that Strachan thinks we are being inconsistent with our appreciation for Aquinas unless we bring him in, wholesale, to every area of ministerial life.

Apart from how dangerously suffocating and schismatic this kind of “all-or-nothing” historical approach would be if applied consistently, it’s worth asking if it is even possible. If I were feeling particularly cheeky, I might respond to Strachan’s challenge with a counter-challenge: “You first. You take your theologians at every point or not at all.” Such a strategy is a quick way to dwindle the number of the faithful theologians down to an army of one. Consistently applying this position personally would leave Strachan-the-Baptist in a profoundly uncomfortable place, having to somehow now justify his appreciative writings of Calvin, Luther, Edwards, and Van Til.

At another point in the podcast, Strachan points out how “Everybody who is embracing Aquinas, who is in any sense a Protestant and doesn’t follow the Pope, would not find Aquinas embracing them if he were living today.” This is true, and I acknowledge it without hesitation. This is not a problem for me, since I feel no compulsion to adopt an all-or-nothing approach when evaluating historical figures. If the fact of Aquinas’s cold shoulder were a problem for me, would there not be an equally difficult problem for Strachan, whose embrace of Zwingli would also not be reciprocated in kind? And if it’s possible for Strachan to appropriate some of Zwingli, and not all (regardless of whether Zwingli would do the same for Strachan) is it not possible for us to do the same with Aquinas?

Confusion of Key Terms

Lastly, I want to point out that for all the words that have been written, tweeted, and recorded, Strachan has not truly entered the debate over the classical retrieval of Aquinas yet. This is perhaps because he misunderstands the key terms of the debate right out of the starting block. Going back to Strachan’s list of disputations against Aquinas, the first of these seven was an objection to Aquinas’s use of apophatic theology. Strachan makes much ado of Aquinas’s language that “we cannot know what God is.” Such a claim is flabbergasting to Strachan, and he objects with all the vigor he can muster. He says this statement is not true because God has revealed himself to us through the Scriptures, and we therefore can know who God is. Of course, Aquinas never said that we could not know who God is in that sense. Aquinas said, rather, that we—finite creatures—cannot know what God is; that is, the essence of God is incomprehensible to us. We finite creatures cannot comprehend the infinite essence of God. This nearly amounts to a tautology: the finite mind cannot comprehend the infinite, since the infinite cannot be circumscribed by the finite.

Aquinas’s denial that we can know the essence of God is simply a rejection of metaphysical univocism (which Strachan seems to presuppose in his reflections on our knowledge of God. If Strachan does not wish to commend a univocism, he would need to explain how he avoids this conclusion, given what he says in this segment of the podcast). Strachan seems to think that by denying univocism—and therefore, the notion that we can know God’s infinite essence—Aquinas rejects all knowledge of God whatsoever. Since we cannot grasp God’s essence, we must not be able to grasp anything about God. But this is a confusion of categories. Such a conclusion is altogether unnecessary, and it is the reason I believe Strachan has misunderstood the key terms. For example, in this segment of the podcast he continually conflates knowing “what” God is with knowing “who” God is (even going back and forth with his language, as if these two very different questions were interchangeable). Strachan insinuates by consequence that Aquinas essentially rejects the notion of divine revelation (or, at the very least, that he is inconsistent with affirming the notion of divine revelation, given his apophatic convictions). This confusing conclusion might be cleared up with the clearing up of Strachan’s category confusion. And then, perhaps, we could begin to have a fruitful conversation.

A Plea for Good-Faith

I do not relish writing a piece like this at all. I feel compelled to write it, however, not only because of the reasons I listed above, but also because of the intense heat of Strachan’s rhetoric displayed persistently throughout the podcast. With Strachan having raised the temperature so high, it is incumbent upon some of us to state explicitly that our appreciation for Aquinas on theology proper does not mean that we want to reverse the Reformation. While he may not say things this starkly, I can imagine a parishioner listening to this podcast and subsequently concluding that theologians and pastors who appreciate Aquinas are on their way to Rome, and are wolves in sheep’s clothing, misleading and consuming the flock. While Strachan may not see anything worth commending in Aquinas, does that mean by consequence that those of us who do are leading Christ’s flock astray?

Let us remember to enter into good-faith dialogue with our opponents. As far as we are able, we ought not make our disputes about personalities or figures (be it contemporary figures or ancient ones like Aquinas). To do this is to put ourselves at risk of committing ad hominem and genetic fallacies over and over again. If we are going to have fruitful debate, we should avoid at all cost mischaracterizations, misdirection, and misunderstanding. To do this, we must turn down the temperature at the interpersonal level, and dial in with precision and sensitivity at the intellectual level.

Editor’s Note: The London Lyceum publishes a range of original pieces and book reviews from various faith traditions and viewpoints. It is not the mission of the London Lyceum to always publish work that agrees with our confession of faith. Therefore, the thoughts within the articles and reviews may or may not reflect our confessional commitments and are the opinions of the author alone. Rather, we seek to generate thinking and foster an intellectual culture of charity, curiosity, critical thinking, and cheerful confessionalism.

Author

-

Samuel G. Parkison (PhD, Midwestern Seminary) is Associate Professor of Theological Studies and Director of the Abu Dhabi Extension Site at Gulf Theological Seminary in the United Arab Emirates. Before coming to GTS, Samuel was assistant professor of Christian studies at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, and pastor of teaching and liturgy at Emmaus Church in Kansas City. He is the author of Revelation and Response: The Why and How of Leading Corporate Worship Through Song (Rainer, 2019), Thinking Christianly: Bringing Sundry Thoughts Captive to Christ (H&E, forthcoming), and Irresistible Beauty: Beholding Triune Glory in the Face of Jesus Christ (Christian Focus, forthcoming)

View all postsRecent Posts