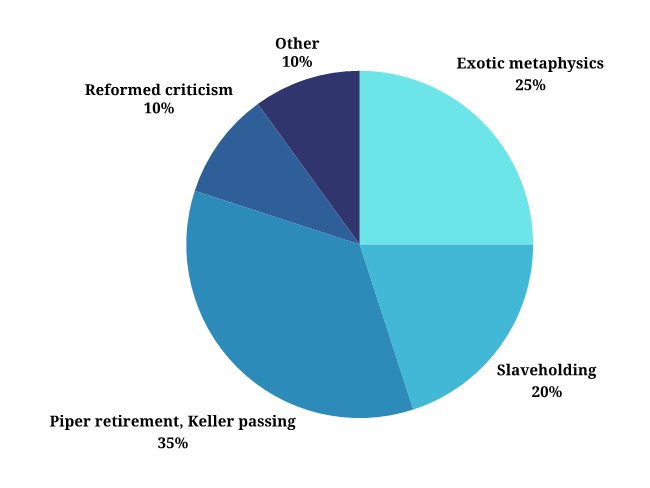

This is not an article on Jonathan Edwards’ culpability as a slaveholder. Nor is this article about all of Edwards scholarship—studies on Edwards’ exegesis and pastoral ministry are, by and large, still going strong. However, a series of factors over the last few years have conspired to severely decrease the interest in reading and writing about Edwards. From our personal experience and conversations as Edwards scholars in European, British, and American university settings, we would carve up these factors in, broadly, the following manner:

We will discuss each of these factors below, but we want to focus on Edwards’ “exotic metaphysics” and how Edwards’ philosophy is received because his philosophical commitments lie beneath all of his exegetical observations and pastoral judgments. In this article we lay out analytic philosophy’s interpretation of Edwards over the last twenty-odd years and why it has led readers today into a dead end.1Thanks to Kenneth Minkema, Doug Sweeney, Oliver Crisp, Kyle Strobel, and John Forcey for their feedback on this article.

First, a word about how this article is laid out. The body of this article is intended to communicate clearly and concisely the problems in Edwards studies, relative to his philosophy, at a lay-level. The footnotes, which are quite extensive, offer more technical details about the state of Edwards’ “exotic” metaphysics that will be of interest to scholars who would like to give Edwards a second hearing.

Edwards’ Exotic Metaphysics

If you have not been keeping up with the general literary output in Edwards studies let’s get you up to speed.2Douglas A. Sweeney, “Edwards Studies Today,” in The Oxford Handbook of Jonathan Edwards, ed. Douglas A. Sweeney and Jan Stievermann (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 569 (=OXJE); Kenneth P. Minkema, “Jonathan Edwards in the Twentieth Century,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 47, no. 4 (2004): 659–87. “At the end of that year, Ken Minkema… reported that the number of secondary publications on Edwards fast approaches 4,000, making him one of the most studied figures in Christian thought and the most studied American intellectual figure before 1800.” Contemporary Edwardsean theologians and historians think Edwards is wrong on, at least, the following topics:

- the nature of cause and effect

- how God created and providentially governs the world

- how to distinguish the Creator from the creature.

The common denominator for all three of these Edwardsean errors is his “hypertrophied” account of divine action.3Oliver D. Crisp, writes: “It is difficult to escape the conclusion that Edwards’ doctrine of God has become hypertrophied at the expense of his doctrine of creation. Human beings and the creation in general are reduced almost to nonentity in some passages, and to shadows in a number of places, in keeping with the Neoplatonism of his thought… creatures are ephemeral, shadowy ideas projected by the divine mind in order to glorify God, which is the ultimate end of creation. It is no wonder that… Charles Hodge regarded his doctrine with suspicion as an incipient pantheism.” In “Idealism,” in The Jonathan Edwards Encyclopedia (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2017), 318 (=JEE); See also: Kyle C. Strobel and Oliver D. Crisp, Jonathan Edwards: An Introduction to His Thought (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2018), 36 (=JEIT); John Carrick, Jonathan Edwards and the Immediacy of God (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2020), 135 (=JEIG).

Regarding (1), Edwards is an occasionalist. This claim means no creature exercises any causal power but is merely the occasion wherein God alone acts. You might have thought that you clicked on this URL, but you didn’t; God did through you. Commitment (2)—his “continuous creationism”—escalates commitment (1) by holding that God must create the universe anew each moment, ex nihilo after ex nihilo after ex nihilo. The image often used to describe this divine activity is that of film stills on a rotating motion picture screen.4Oliver D. Crisp, Jonathan Edwards on God and Creation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012) 25 (=JEGC). “Edwards couples [occasionalism] with a doctrine of continuous creation. This is the view according to which God creates the world out of nothing, whereupon it momentarily ceases to exist, to be replaced by a facsimile that has incremental differences built into it to account for what appear to be motion and change across time. This, in turn, is annihilated, or ceases to exist, and is replaced by another facsimile world that has incremental differences built into it to account for what appear to be motion and change across time, and so on.” See also Strobel and Crisp, JEIT 36. Frame by frame, the film gives the impression of action, but in reality, each still or frame is inert and unmoving, recreated by God each moment at a time.5According to Crisp, “since strictly speaking nothing persists through time according to this Edwardsian doctrine of continuous creation, and since God is the sole causal agent at work in the creation, any appearance of physical constants persisting from one moment to the next is illusory.” JEGC 31. Again, Crisp says, “In addition, no created being is a causal agent, strictly speaking, because no created being exists for long enough to cause any given act.” JEGC, 32. Crisp again asserts that “we have already seen that Edwards’ endorsement of the doctrines of continuous creation and occasionalism means that what is created does not persist through time. Strictly speaking, ‘the world’ is shorthand for the infinite number of numerically distinct but qualitatively similar world-stages God creates ex nihilo, and segues together into a series of his own making. This entails the denial of the endurance of created object. Things that appear to persist through time do so only by divine fiat…” JEGC, 185. Together, Crisp and Strobel argue that, “As far as Edwards was concerned, in the strictest sense nothing exists independent of the divine mind and its mental contents. All created things, including created minds, exist as ideas in God’s mind or as ideas projected by God’s mind (like the projection of a motion picture onto the screen of a movie theater).” JEIT 73 (=JEIT). Robert Letham, Systematic Theology (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2019), 293. “Providence is also opposed to occasionalism as taught by Jonathan Edwards. Edwards held that God creates the world every nanosecond.” When (1) and (2) are combined, God becomes the only causal author, which in turn means that he is inescapably the author of all sins.

If this seems too bizarre to be true, then you will want to stay away from the last twenty years of literature on Edwards’ philosophy.6For the pervasive references to Edwards’ “flip book” ontology, see the following: Oliver D. Crisp and Paul Helm, eds., Jonathan Edwards: Philosophical Theologian (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2003), xiii, 75 (= JEPT); Strobel and Crisp, JEIT, 73-74, 109-16, 119, 207, 210-11; Oliver D. Crisp, Jonathan Edwards and the Metaphysics of Sin (Farnham, England: Ashgate, 2005), 131-33 (=JEMS); Oliver D. Crisp, Jonathan Edwards on God and Creation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 9, 25–26, 85–86, 89–90, 92, 160, 162 (=JEGC); Oliver D. Crisp, Jonathan Edwards Among The Theologians (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2015), 13, 28, 75 (=JEAT); Oliver Crisp, Revisioning Christology: Theology in the Reformed Tradition (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011), 56; Oliver D. Crisp, “Jonathan Edwards,” in The Cambridge Companion to Reformed Theology, ed. Paul T. Nimmo and David Fergusson, Cambridge Companions to Religion (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 158–59; Oliver D. Crisp, “Occasionalism,” in JEE 415-19. Given the transitory, apparition-like nature of creatures on (1) and (2), commitment (3) should come as no surprise. This refers to Edwards’ panentheism. A panentheist—as defined by the literature—is a thinker who holds to a weak ontological distinction between the Creator and the creature. This means that the world exists “within” God or, in metaphorical language, God is a kind of “soul of the universe.”7John W. Cooper, Panentheism: The Other God of the Philosopher from Plato to Present (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2013), 74-77. Historically speaking, this is also similar to panpsychism, which was a line of thinking common in Platonic circles.8Arthur O. Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, [1933] 1982).

Retrieving an “Exotic,” “Unhinged” Edwards?

The good news for Edwards is that “retrieval” projects are all the rage, especially among evangelicals.9John B. Webster, “Theologies of Retrieval,” in The Oxford Handbook of Systematic Theology, ed. John B. Webster, Kathryn Tanner, and Iain Torrance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 583–99. A contemporary example is Dane C. Ortlund, Edwards on the Christian Life: Alive to the Beauty of God, Theologians on the Christian Life (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2014). Ortlund mentions none of the problematic issues that Carrick raises as relevant for the “Edwards of Faith.” The bad news for Edwards scholars is that no one wants to retrieve an occasionalist, a continuous creationist, and panentheist theology. Seriously, which theologians and pastors look at these fundamental commitments on cause and effect, God and creation, as correct? Who wants to endorse these models of God? No one.10Some philosophers might endorse one of these positions, but not all of them bundled together. And no evangelical readers or theologians that we know of would endorse all three features combined. For example, Alvin Plantinga endorses a “weak occasionalism” as a compromise for having “no clear conception of causation as accomplished by creatures.” But Edwards endorses “strong occasionalism.” Plantinga, “Law, Cause, and Occasionalism,” in Reason and Faith: Themes from Richard Swinburne, ed. Michael Bergmann, First edition (Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, 2016), 126–44; David K. Lewis endorses a kind of four-dimensionalism about time that can be connected to continuous creation. See Lewis, “The Paradoxes of Time Travel,” in Philosophical Papers, vol. 2, 2 vols. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 67–80. Support for Panentheism has been common amongst post-Hegelian Mainline Protestant theologians like Philip Clayton. That population has not found Edwards particularly interesting. See Clayton, ed., In Whom We Live and Move and Have Our Being: Panentheistic Reflections on God’s Presence in a Scientific World (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2004). All the philosophers studying Edwards on these subjects think he is wrong.

That so many Edwards scholars think he is wrong about these things is an understatement. More accurately, Edwards is regarded as “exotic” and “unhinged” on these matters. Here are fourteen individual statements—derived from both contemporary and historic readings of Edwards, academic and popular alike—that demonstrate just how bizarre Edwards is understood to be:

Over the centuries, many [scholars] have advanced philosophical reasons for rejecting Edwards’ occasionalism…. Perhaps Edwards should be faulted less for making God the author of evil than for speculating on deep and perhaps unanswerable questions.11Michael J. McClymond and Gerald R. McDermott, The Theology of Jonathan Edwards (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 355-56 (=TJE).

Maybe Edwards’ drift towards occasionalism and an anti-realist ontology that ultimately makes the world a kind of “magic lantern show,” a projection of divine ideas from God, can also be understood as a reaction to the perceived danger of a [rising] secularism.12Jan Stievermann, “History, Providence, and Eschatology” in OXJE, 232.

This [continuous creation] belief is susceptible to the charge of ultra-supernaturalism on Edwards’ part, and it constitutes, in the sheer counter-intuitiveness that attaches to it, a species of metaphysical enthusiasm…. It would not be improper to claim… that continuous creation falls, under the category of what Locke aptly describes as “the ungrounded fancies of a man’s own brain.”13Carrick, JEIG 135.

I say, [continuous creation] … is as wild a conceit of a vain imagination as was ever published to the world. It cannot be paralleled with anything, unless the doctrine of transubstantiation.14Charles Chauncy, Five Dissertations on the Scripture Account of the Fall and Its Con

[Edwards] can easily swallow the gnat of [divine] sovereignty because he has already devoured the camel of pure idealism. Surely Edwards needed to be an idealist to assure himself that his theory of sovereignty was more than a pious fiction or feeling.15Michael J. Colacurio, “The Example of Edwards: Idealist Imagination and the Metaphysics of Sovereignty,” in Emory Elliott, ed. Puritan Influences in American Literature (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1979), 64.

[For Edwards], we exist as divine ideas that are projected on the movie theater screen of the divine mind in a series ordered according to God’s will. This is brought out most clearly in… “The Mind” notebook as well as The End of Creation, where his monomania about preserving the absolute sovereignty of God from any encroachment by creatures means that he ends up undermining created agency… The cost of preserving God’s sovereignty in Edwards’ case is implicating the Deity as the author of sin and evil, a cost that most Christian theists will find too high.16Crisp, JEE, 418.

[Edwards] was color blind to everything but the sin of man and the “sovereignty” of God… how can we explain this? We find our explanation then in the fact that Jonathan Edwards was a theological monomaniac. He was afflicted with a species of delusional insanity, which took possession of him in his early youth, and which had its centre in the dogma of “Divine sovereignty.” When his mind turned to that subject, his faculties were preternaturally active, but this activity was a as morbid as that of many a disordered mind.17 Joseph H. Crooker, “Jonathan Edwards: A Psychological Study,” New England Magazine, 1890, 167–68.

One of the greatest of all errors is the attempt to exalt God by making him the sole cause, the sole agent in the universe, by denying to the creature freedom of will and moral power, by making man a mere recipient and transmitter of a foreign impulse. This… destroys all moral connection between God and his creatures… To extinguish the free will is to strike the conscience with death, for both have but one and the same life. It destroys responsibility. It puts out the light of the universe; it makes the universe a machine. It freezes the fountain of our moral feelings, of all generous affection and lofty aspirations. Pantheism, if it leaves man a free agent, is a comparatively harmless speculation… The denial of moral freedom, could it really be believed, would prove the most fatal of errors. If Edwards’ work on the will could really answer its end—if it could thoroughly persuade men that they were bound by an irresistible necessity, that their actions were fixed links in the chain of destiny, that there was but one agent, God, in the universe—it would be one of the most pernicious books ever issued from our press. Happily, it is a demonstration that no man believes, which the whole consciousness contradicts.18William Ellery Channing, “Introductory Remarks,” The Works of William E. Channing D. D. Vol. IV (Glasgow: James Hedderwick & Son, 1844), 16 (https://books.google.com/books?id=52RVAAAAcAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false).

Edwards was… a “God intoxicated theist.” He was so committed to the absolute sovereignty of God over all that God has created that he went to great lengths to preserve that sovereignty in the face of what he would have thought of as potential avenues by means of which God’s exalted status might be eroded or undermined by his creatures. But the cost of Edwards’ vision of God is that human agency appears to be a very meagre thing indeed, and God appears to be morally responsible for sin. For although he speaks of human moral responsibility in Freedom of the Will, from his other works it is clear that no creature persists from one moment to the next in order to perform any of the actions he imputes to them. Created persons are just conglomerations of instantaneous stages aggregated across time. It is very difficult to see how one can salvage a robust account of creaturely moral responsibility from a view like that. For it means that no creature exists long enough to be able to complete an action for which the creature may be held morally responsible.19Strobel and Crisp, JEIT, 120.

This doctrine of a continued creation destroys the Scriptural and common sense distinction between creation and preservation… The two ideas are essentially distinct. Any theory, therefore, which confounds them must be fallacious. God wills that the things which He has created shall continue to be; and to deny that He can cause continuous existence is to deny his omnipotence.20Charles Hodge, Systematic Theology, 3 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1885), 2.1.219.

[Edwards’] doctrine of continuous creation is a dumpster fire… If you want to be a faithful Edwardsean, you will have to reject him on several key things, including this continuous creation [doctrine].21Kyle Strobel, interviewed by Jordan Steffaniak, “Infused and Acquired Virtues with Kyle Strobel,” 46:06, posted February 12, 2025, https://open.spotify.com/episode/3FiFwXxizBelMdJCaI6Mp6?si=d16ba94287d54460.

Here’s a task for scholars: find the first glimmer in Edwards’ theology of continual creationism, and read the notebook where it arises, and let’s find out what he ate that day and maybe the night before. Maybe bad indigestion was creating delusions in Edwards.22Camden Bucey, “John Carrick – Jonathan Edwards and the Immediacy of God,” Reformed Media Review, 15:50, posted November 9, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dPBhPyrquGc.

In the final analysis, God is alone in Edwards’ metaphysics “talking to a reflection of himself in a mirror” as [Thomas] Schafer puts it.23JEGC, 202n.62 citing Thomas Schafer, “Editor’s Introduction” in WJE 13.49. Schafer writes, “One way of reading this metaphysical analysis is that, instead of guaranteeing the value and immortality of intelligent creatures, Edwards’ doctrine of perception leaves God finally alone, talking to a reflection of himself in a mirror. That, of course, was not Edwards’ intention, but it is curious that he never seems to have been aware of this potential objection.” See also Oliver D. Crisp, “Jonathan Edwards on Creation and Divine Ideas” in Kyle C. Strobel and Chris Chun, eds. Regeneration, Revival, and Creation (Eugene: Pickwick, 2020), 199–200.

As [Edwards] argued in Original Sin and throughout his Miscellanies, God continually recreates the world every second, and God himself is the reality sustaining all of creation. Nothing exists apart from God’s continual recreation of it, and the substance of every existent thing is God’s knowing and willing of that thing. God is the substance even of heaven and of hell.24TJE, 6.

With Edwards specialists like these, who needs enemies?

Notice that we snuck in a few of Edwards’ sworn enemies—Charles Chauncy and William Ellery Channing—into the above quotations. The point of this exercise is to show that we are at a topsy-turvy moment in Edwards studies where Edwards opponents and Edwards specialists actually agree that America’s purportedly greatest theologian is altogether “unhinged” on basic matters of philosophy.

Thesis

Building upon the central claim of this article—Edwards studies is at a dead end—we offer up the following state-of-the-field update to lay readers and, what is more, a call to arms. To that end, the remainder of this article is broken up into three sections. In the first section, we discuss why awareness of Edwards’ exotic metaphysics has not trickled down into more lay or popular readings. Call this the “Edwards of Faith” section, influenced by pastors like John Piper and Tim Keller.25We are borrowing and building on R. Bryan Bademan’s 2006 taxonomy in “The Edwards of History and the Edwards of Faith,” Reviews in American History 34. 2 [2006]: 131–49. The “Edwards of Faith” can be distinguished from – and it not be necessarily opposed to – the more complicated “Edwards of History.” Bademan rightly notes that, “these constituencies overlap in important ways, but at their extremes are significant tensions in historical understanding,” 139-40. In the second section, we quickly survey the last two decades of Edwards scholarship by analytic philosophers and analytic theologians. This is the “Edwards of (Analytic) Philosophy” section.26Edwards has not had Continental readers outside of the following: William Harder Squires, The Edwardean: A Quarterly Devoted to the History of Thought in America, ed. Richard Hall (Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1991); Miklos Veto, The Thought of Jonathan Edwards, trans. Philip Choinière-Shields, Jonathan Edwards Classic Studies Series (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2021). We strongly disagree with this interpretation.

Of course, we cannot trace all of the above stated problems in Edwards scholarship. Instead, we purposefully limit our conceptual center of gravity, so to speak, to the occasionalism and continuous creation features of Crisp’s account of Edwards.27We are not addressing the necessitarian (or justification) objections facing Edwards for two reasons. First, unlike the occasionalism and continuous creation objections, the necessitarian and justification objections have thoroughly engaged the “Edwards of History” and his historical context, which make addressing the objection more technical. For the debate, start with Richard A. Muller, “Jonathan Edwards and the Absence of Free Choice: A Parting of Ways in the Reformed Tradition,” Jonathan Edwards Studies 1, no. 1 (2011): 3–22; Paul Helm, “Jonathan Edwards and the Parting of the Ways?,” Jonathan Edwards Studies 4, no. 1 (2014): 42–60; Philip John Fisk, Jonathan Edwards’ Turn from the Classic-Reformed Tradition of Freedom of the Will, New Directions in Jonathan Edwards Studies 2 (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2016); J. V. Fesko, Justification: Understanding the Classic Reformed Doctrine (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2008), 34-9. Second, the issue of necessitarianism has not featured as prominently in Crisp and Strobel’s scholarship. It seems to us that Strobel and Crisp assent to Muller’s reading of Edwards. Strobel recently reported that “one way to read Edwards would be that he’s a kind of determinist who messes up the Reformed account of compatibilism – although that’s probably true admittedly.” Strobel, Zachary Bodwen, and Brandon D. Smith, “Jonathan Edwards (If You Can Keep Him),” Church Grammar, 12:30, posted September 13, 2023, https://open.spotify.com/episode/6Ti9kIcznavWSYrsVd9WaJ?si=a841e67b342a4e0a. See also JEIT, 116-118; JEGC 209n.2. Crisp was never really interested in Edwards’ modal distinctions: “We shall have to take Edwards at his word on this notion of ‘moral’ necessity. He distinguishes between several kinds of necessity in Freedom of the Will [Parts] I, III, and IV, but not altogether clearly. An examination of these concepts is not possible here.” JEMS, 94n.25. Crisp never examined these distinctions in subsequent writings. In a third section, we show how a recent attempt to fuse the popular, “Edwards of Faith” with the “Edwards of Philosophy” went haywire in John Carrick’s Jonathan Edwards and the Immediacy of God (2020). We chose this book because it concisely, honestly, and transparently exhibits the problematic trends in the current analytic interpretation of Edwards. Carrick also shows us that the current analytic interpretations force us to choose between Edwards being wildly ignorant or a liar. Finally, in our concluding section, we give reasons to be hopeful with a return to the “Edwards of History,” represented by scholars like William Morris and Norman Fiering, Kenneth Minkema, Peter Thuesen, and Douglas Sweeney.

At this point, you are likely thinking: “But if this article is a literature review, why not publish it in an academic journal?” The short answer is that we want a wider, non-academic audience to be aware of this call to arms. For, this is not the first time warning bells have been rung. That honor belongs to Crisp’s 2014 article: “On the Orthodoxy of Jonathan Edwards.”28Oliver D. Crisp, “On the Orthodoxy of Jonathan Edwards,” Scottish Journal of Theology 67, no. 3 (2014): 304–22; Crisp, JEAT chap. 9. Crisp might have more accurately entitled this piece “On the Heterodoxy of Jonathan Edwards.” Maybe then scholars might have heard the bell toll. Alas, that call was ignored, despite Crisp’s argument being characteristically clear and simple: Edwards’ writings about God and creation have profound contradictions in them. More specifically, Crisp’s argument was that Edwards claims to subscribe to divine simplicity, but his additional commitments to occasionalism, continuous creationism, and panentheism force him into an insuperable dilemma. Either God is not metaphysically simple, or the latter commitments force him towards pantheism.29Nearly all of Crisp’s criticisms, including their interconnectivity were raised first by William Ellery Channing in 1841 – including the specter of pantheism. “From such views [of divine sovereignty] naturally sprung Pantheism. No being was at last recognized but God. He was pronounced the only reality. The universe seemed a succession of shows, shadows, evanescent manifestations of the One Ineffable Essence. The human spirit was but an emanation, soon to be reabsorbed in its source. God, it was said, bloomed in the flower, breathed in the wind, flowed in the stream, and thought in the human soul. All our powers were but movements of one infinite force. Under the deceptive spectacle of multiplied individuals intent on various ends, there was but one agent. Life, with its endless changes, was but the heaving of one and the same eternal ocean… In Protestantism, the same tendency to exalt God and annihilate the creature has manifested itself, though in less pronounced forms. We see it in Quakerism and Calvinism, the former striving to reduce the soul to silence, to suspend its action, that in its stillness God alone may be heard; and the latter, making God the only power in the universe and annihilating the free will, that one will alone may be done in heaven and on earth. Calvinism will complain of being spoken of as an approach to Pantheism. It will say that it recognizes distinct minds from the Divine. But what avails this if it robs these minds of self-determining force, of original activity; if it makes them passive recipients of the Universal Force; if it sees in human action only the necessary issues of foreign impulse? The doctrine that God is the only Substance, which is Pantheism, differs little from the doctrine that God is the only active power of the universe. For what is substance without power? It is a striking fact that the philosophy which teaches that matter is an inert substance and that God is the force which pervades it has led men to question whether any such thing as matter exists—whether the powers of attraction and repulsion, which are regarded as the indwelling Deity, be not its whole essence. Take away force, and substance is a shadow and might as well vanish from the universe. Without a free power in man, he is nothing. The divine agent within him is everything. Man acts only in show. He is a phenomenal existence, under which the One Infinite Power is manifested; and is this much better than Pantheism?” Channing, “Introductory Remarks,” 13–16. To date, not a single scholar has picked up Crisp’s gauntlet, either by challenging Crisp’s account of Edwards or by modifying and defending Edwards himself.30All the citations we could find only restate that Edwards has major philosophical problems; they offer no solutions. Among the former, the best example is Walter J. Schultz, Jonathan Edwards’ Concerning the End for Which God Created the World: Exposition, Analysis, and Philosophical Implications, New Directions in Jonathan Edwards Studies, volume 6 (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2020), chap. 10; Scott Cook, “More Modern than Orthodox? Charles Hodge and the Doctrine of God,” in Charles Hodge: American Reformed Orthodox Theologian (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2023), 113; Joseph J. Rigney, “Diverse Excellencies: Jonathan Edwards on the Attributes of God” (Chester, UK: University of Chester, 2019), 66n.227, https://chesterrep.openrepository.com/handle/10034/622860; Jordan P. Barrett, Divine Simplicity: A Biblical and Trinitarian Account, Emerging Scholars (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2018), 106 (n.57); Robert Letham simply accepts Crisp’s reading entirely in his Systematic Theology, 293. By this light, this article is a less technical version of Crisp’s call to arms (at least in the body of the text)—one we hope is not ignored. Enter the “Edwards of Faith.”

I. The Edwards of Faith

The “Edwards of Faith” is likely to be well known among followers of the London Lyceum. Edwards is the relentless preacher of evangelical truths, the defender of the Great Awakening, the towering intellect whose sermons and scriptural notes line the bookshelves of Millennial pastors who were endeared to Edwards because of the ministries of John Piper or Tim Keller.31Colin Hansen, Young, Restless, and Reformed: A Journalist’s Journey with the New Calvinists (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2008). This is also the “Banner of Truth Edwards,” so to speak. That is, the college kids and pastors who, reluctant to purchase the expensive Yale volumes, trudged through the painfully small double-column print to understand Piper and Keller’s inspiration.32Bademan recorded that between Presbyterian and Reformed, Banner of Truth Trust, and Crossway, over 35,000 copies of The End for Which God Created the World were sold by the end of the year 2004. Bademan, “The Edwards of History and the Edwards of Faith,” 144–45. We have both heard Edwards scholars scoff at these readers after a beer or two. But such academics shouldn’t kid themselves, for these are the readers that keep Religious Affections and Freedom of the Will on the Amazon bestseller list in theology to this day.

It is no stretch to say there is no “Edwards of History” or “Edwards of Philosophy” without the “Edwards of Faith” readership. How many secular undergraduates come into universities today with an intrinsic interest in pre-Revolutionary American religious thought? Whatever that number is, it will never be the size of the pipeline of readers coming from people who read The Gospel Coalition. Edwards scholars need a steady stream of the latter to sustain teaching and publishing interest in Edwards at the scale it has been running since 2003.

2003: The Rising Tide

At the tercentenary of Edwards’ birth (2003), historian Doug Sweeney heralded it as the “most important year ever in the history of Edwards studies.” Many of the evangelicals—hooked on Edwards or American (religious) history through Piper and Keller—were handed off to academic mentors like George Marsden and Mark Noll.33Bademan, 145. Between 1980 and the early 2000s, there was a large influx of young evangelical talent into academia by those who “hailed Edward as the luminary of their tradition, someone who made a lasting contribution to American intellectual life while remaining resolutely pious.” Marsden’s award-winning biography of Edwards was published during that same year. Noll’s magisterial survey of American historical theology—America’s God—was published the fall before that.34Bademan, 137. At the time, there were clear on-ramps from the “Edwards of Faith” into academia.

This 2003 tide seems to have been broken into two tributaries.35Douglas A. Sweeney, OXJE, 568-69. Sweeney offers a more institutional analysis of the surge in Edwards studies, begun with Perry Miller and the Yale edition, carried through by Harry Stout and Kenneth Minkema, into various academic departments today – literature, history, cultural studies, and philosophy. The first tended towards the Edwards of analytic philosophy, which we discuss in the next section. The second tended towards Edwards’ exegesis and pastoral practices, a more natural environment for evangelicals which has continued to flourish.36Robert E. Brown, ed., Jonathan Edwards and the Bible (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002); Douglas A. Sweeney, Jonathan Edwards and the Ministry of the Word: A Model of Faith and Thought (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009); Stephen R. C. Nichols, Jonathan Edwards’ Bible: The Relationship of the Old and New Testaments (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2013); Daivd S. Lovi and Benjamin Westerhoff, eds., The Power of God: A Jonathan Edwards Commentary on the Book of Romans (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2013); David P. Barshinger, Jonathan Edwards and the Psalms: A Redemptive-Historical Vision of Scripture (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014); David P. Barshinger and Douglas A. Sweeney, eds., Jonathan Edwards and Scripture: Biblical Exegesis in British North America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018); Gilsun Ryu, The Federal Theology of Jonathan Edwards: An Exegetical Perspective, Studies in Historical and Systematic Theology Series (St Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2021); Brian Borgman, Jonathan Edwards on Genesis: Hermeneutics, Homiletics, and Theology (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2021); Joseph T. Cochran, Jonathan Edwards and Hebrews: A Harmonic Interpretation of Scripture, New Directions in Jonathan Edwards Studies (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2025), https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666560958; David Van Brugge, That Which They Can’t See: A Retrieval of Jonathan Edwards’ Homiletical Use of Imagination, Reformed Historical Theology (Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2025), https://doi.org/10.13109/9783666502088; Cameron Schweitzer, Towards a Clearer Understanding of Jonathan Edwards’ Biblical Typology: A Case Study in the ‘Blank Bible’ (Fort Worth, TX: JESociety Press, 2025). There is also a great deal of work being done on the “Visual Edwards” and translations of Edwards into international languages that will certainly keep the “Edwards of Faith” interest afloat.37Thanks to Kenneth Minkema for this observation. Rob Boss’ herculean effort to visualize Edwards is one of the most remarkable resources in the history of Edwards studies: https://www.jesociety.org. One example of Edwards translation efforts is catalogued in Herber Carlos De Campos Jr.’s “Latin America,” OXJE, 564–67. The leading scholar on Edwards’ exegesis, Doug Sweeney, made the point that Edwards perused his exegetical sources (e.g., Cotton Mather, Matthew Henry, John Owen) “more frequently than Locke, Berkeley, Newton, Malebranche” and others who have typically drawn the most attention in Edwards studies.38Sweeney, OXJE, 577.

In terms of counting citations and sources, Sweeney is absolutely correct. However, the reason why—by our lights—philosophers like Berkeley and Malebranche matter disproportionately for Edwards studies is because it is (purportedly) from these sources that Edwards grabs ahold of his exotic, unhinged theories of occasionalism and continuous creationism. While Edwards’ exegetical insights might be edifying to us today, how many of them touch upon causation—divine or human? And should exegetical scholars continue to ignore Edwards on causation?

2020: The Tide Goes Out

Anecdotally speaking, since 2003, the high tide of Edwards scholarship seems to be receding. We can offer at least three pieces of evidence for this.

First, consider the Oxford Handbook of Jonathan Edwards (2021), which is a compendium of the best scholarship on Edwards’ sources, context, philosophy, theology, spirituality, missions, and legacy. For a scholar to contribute here is a kind of crowning moment for their Edwards career. Of the thirty-nine contributors, nine have completed their work on Edwards and moved onto other projects. Ten more are either emeritus or approaching retirement. One has since passed away. Only seven contributors are established senior scholars—that this, they enjoy an economically secure post in an academic institution and are continuing to work on Edwards or American evangelicalism more broadly. Astonishingly, the other seven contributors—among the youngest of the contributors to the Handbook—are either independent scholars or effectively outside of the academy.39Five other contributors were not Edwards specialists, but work in adjacent fields like English, aesthetics, or the history of religion in Asia, Australia, or Latin America. While this might be the norm in the higher education downturn, it is certainly not an ideal arrangement for the next generation of Edwards scholarship. Crisp notably refrained from contributing to the Handbook altogether and appears to be done writing on Edwards.40Crisp has made it clear in personal correspondence that he will spend his foreseeable literary future working, almost exclusively, on a multi-volume systematic theology, not Edwards.

The second reason for thinking the tide of Edwards scholarship is receding has to do with Edwards’ slaveholding. In our experience, this seems to be the most significant factor in diverting evangelical interest away from Edwards at major American universities like Yale, Notre Dame, and Princeton. Since 2020, evangelical readers and students have been scandalized as they learned that Edwards was a lifelong slaveholder. Much to their credit, their disappointment is usually sincere and earnest. How could America’s greatest theologian—someone who shares their faith—reduce another human being into mere property?41For a recent treatment, see Sean McGever, Ownership: The Evangelical Legacy of Slavery in Edwards, Wesley, and Whitefield (Westmont: InterVarsity Press, 2024). Secular students, by contrast, tend to shrug their shoulders in cynicism, making it all the more difficult to motivate serious discussion around Edwards and the Puritans in the classroom.

The third reason why Edwards scholarship is drying up—the reason we are focusing on here—is that readers of the “Edwards of Faith” simply don’t know what to do with Edwards’ basic philosophical commitments. The exemplar we will use for this instance is Carrick’s work below.

To summarize, the “Edwards of Faith” generates an evangelical pipeline of scholars who tend to be most interested in Edwards’ exegesis and pastoral practice. Due to justified objections against Edwards’ unrepentant slaveholding, this first pipeline appears to be drying up at the universities that were once major producers of Edwards scholars. Yet another, smaller portion of the 2003 tide opted for the second tributary: the “Edwards of Philosophy.” Let’s look at what happened to their ideas.

II. The Edwards of (Analytic) Philosophy

To dominate an academic field, a necessary condition is to be in the right place at the right time. As analytic theologians, Paul Helm and Oliver Crisp were perfectly positioned to lead research on Edwards’ philosophy in the early 2000s and 2010s. At the height of the “Young, Restless, and Reformed” movement, if you were an evangelical intimidated (or out-priced) by Edwards’ Freedom of the Will or Original Sin, you picked up something—often uncritically—by Helm and Crisp.42For Edwards’ influence, see Hansen, Young, Restless, and Reformed, chap. 3. For an autopsy of the movement, see Brad Vermurlen, Reformed Resurgence: The New Calvinist Movement and the Battle over American Evangelicalism (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2020). Even in 2008, it was possible to see reasons for an Edwards slowdown. For example, Hansen writes: “As much as I enjoy reading Edwards, I told [Josh] Moody that I doubt we’ll ever again see his writing reach the bulk of evangelicals, as it did during the Great Awakening. My marked-up copy of Religious Affections runs nearly four hundred pages in the Banner of Truth version. And that’s one of his more accessible works. I haven’t yet dared to pick up Freedom of the Will.” It would be too strong to say that Helm and Crisp’s interpretation ran unopposed during this period. There were dissenters, albeit no more than three.43Unpacking why would require another article, which is a work in progress. At present, there are only three extant rebuttals of (or amendments to) the occasionalist reading of Edwards: Sweeney, Wilson, and Hamilton. Douglas Sweeney, “Editor’s Introduction,” The Works of Jonathan Edwards (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2004), 23.20–23 (=WJE); Stephen A. Wilson, Virtue Reformed: Rereading Jonathan Edwards’ Ethics, ed. A. J. Vanderjagt, Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History 132 (Boston: Brill, 2005), chap. 3 “The Integrity of Secondary Causes,” esp. 148–52, 180–81. Wilson rightly argues “[The occasionalist] line of interpretation does not, however, stand up to closer scrutiny. The strongest case for Edwards’ occasionalism yet made [i.e., Crisp JEPT and JEMS] must in the end admit some of the textual evidence is based on interpretations that have equally plausible non-occasionalist readings.” S. Mark Hamilton, A Treatise on Jonathan Edwards, Continuous Creation and Christology (Fort Worth, TX: JESociety Press, 2017), ch.3. During the early 2000s there was a dispute between the so-called “Lee school” and the approach of Crisp, Strobel, and Stephen Holmes to interpreting Edwards. We will not cite all of that literature here. See McClymond and McDermott, TJE 102–4; Crisp and Strobel, JEIT, 91–93, 113–14. In theory, there was a sufficient supply of “Jonathan Edwards is my homeboy” readership—academic and laity alike—that some sector of this population should have been concerned about Crisp’s heterodox Edwards in 2014. Alas, this never materialized. To fully explain why it never materialized would require going back to the start of analytic readings of Edwards (c. 1971), but space forbids doing that. Instead, we will provide a thumbnail sketch of the “Edwards of (Analytic) Philosophy” since 2003.

2003—2005: Laying the Foundation

Crisp’s interpretation has, by and large, set the standard for interpreting Edwards’ metaphysics since he edited Jonathan Edwards: Philosophical Theologian (2003) with his then doctoral supervisor, Paul Helm. Crisp’s inaugural publication, “How Occasional was Edwards’ Occasionalism?” was an interpretation (contra Sang Lee) that Edwards was a defender of occasionalism. Helm’s contribution to this collection covered Edwards and Locke’s theories of personal identity, something he continued writing about for the next several years. In that article, Helm articulates the most radical version of continuous creationism, writing that “[d]espite Edwards’ very strong avowal of divine sovereignty it would seem that not even God can preserve in existence for more than a moment a being as numerically identical being or as one that has numerically identical parts through that period of time.”44Paul Helm, “A Forensic Dilemma: John Locke and Jonathan Edwards on Personal Identity,” in JEMS, 54; Paul Helm, “Jonathan Edwards on Original Sin,” in Faith and Understanding, Reason & Religion (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 166. Thankfully, this divine ineptitude version of continuous creation was not picked up by Crisp and carried down the analytic river.

Crisp then went on to publish his doctoral dissertation, Jonathan Edwards and the Metaphysics of Sin (2005), which hitherto contains his most technical and detailed reading of Edwards. Chapter seven of this volume, “The Problem with Occasionalism,” is arguably the most important feature in that work. Crisp concludes that Edwards’ occasionalism was “the fatal flaw” in his metaphysics because it holds that “God is the sole moral agent… no creature is morally responsible for their actions.”45Crisp, JEMS, 130-31. Thus, “it appears that Edwards’ God is the author of sin.”46Crisp, JEMS, 134. Crisp cites Helm throughout his book in support of this reading and there appears to be nothing in Helm’s writings (to date) that seriously dissents from Crisp’s occasionalism and continuous creationism interpretation.

One of the first non-analytic scholars to take notice of the implications for Crisp’s new Edwards was Elizabeth Agnew Cochran. In a 2005 book review, she rightly read Crisp as suggesting that to be Edwardsean after Edwards, one must remove his occasionalism, which is unfortunately “central to his metaphysics.”47Elizabeth Agnew Cochran, “Oliver Crisp, Edwards and the Metaphysics of Sin (Review),” Scottish Journal of Theology 63, no. 2 (2010): 241–43, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0036930607003559. She also critiqued Crisp for reading Edwards “more or less in isolation from specific works of his contemporaries… [which] would fruitfully highlight other nuances in [Edwards’] position.” Interestingly, this is exactly the task Strobel calls other Edwards scholars and readers to execute in his final chapter “Becoming Edwardsean” Strobel and Crisp, JEIT, chap. 8. Then, as nearly the entire field is inclined to do, Cochran went on to write a book—Receptive Human Virtues: A New Reading of Jonathan Edwards’ Ethics (2011)—that simply whistled by Edwards’ otherwise unhinged accounts of cause and effect, divine and human action.48To her credit, Cochran attempt to rebut Crisp’ claim that Edwards makes God the author of sin, but she never addresses the causal aspects of his argument, only necessity and intentionality. She does mention “continuous creation” once later on, but only in passing as a notable difference between Calvin and Edwards. Cochran, Receptive Human Virtues: A New Reading of Jonathan Edwards’ Ethics (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011), 36–37, 140. This “whistling by” is a reoccurring strategy with the “Edwards of Philosophy.” Theologians and historians don’t really know what to do with Edwards’ occasionalism, so they simply pretend it isn’t the leading interpretation for how Edwards’ thinks about the world. Crisp later interacted with Cochran in his “Moral Character, Reformed Theology, and Jonathan Edwards” (2017), which reminded ethicists that the problems of occasionalism and continuous creation were still problems and added the problem of theological voluntarism as an update.49Crisp, “Character, Reformed Theology, and Jonathan Edwards,” Studies in Christian Ethics 30.2 (2017): 273-277. Shockingly, ethicists haven’t exactly been clamoring to use this Edwards in projects of retrieval or moral theology.

2012—2016: Growing Concerns

Crisp’s stark conclusions—occasionalism as fatal flaw and God as the author of sin—are somewhat muted in his Jonathan Edwards on God and Creation (2012). And yet another new problem emerges: Panentheism. The panentheism debate initially emerged as a question over whether Edwards subscribed to a classical doctrine of simplicity, but in his chapter on the subject, Crisp assembles Edwards’ panentheism, emanationism, idealism, continuous creationism, and occasionalism together. The combination of these “exotic” ideas prompts the question: “Is Edwards a classical theist?50Crisp, JEGC, 142–51, 160-63. Of course, this is not an easy question to answer. Hence Crisp’s 2014 article, “On the Orthodoxy of Jonathan Edwards,” wherein occasionalism, continuous creation, and panentheism don’t just threaten creaturely causality, they threaten to deny that God is metaphysically simple. Still worse is that Edwards is a short slide away from becoming a pantheist—identifying God with the created world! In his last entries on Edwards for the Jonathan Edwards Encyclopedia (2017), Crisp has not changed his views. If anything, Edwards’ exotic commitments seem worse today than a decade ago.51Crisp: “In The End, Edwards so exalts divine sovereignty over the creation that he ends up endorsing a doctrine of panentheism… In creating this series of world stages, God emanates the world. It is like a shadow that he casts… That is a very thin doctrine of the being of creation indeed.” “Idealism,” in JEE, 315-18; Crisp: “[Edwards’] monomania about preserving the absolute sovereignty of God from any encroachment by creatures means that he ends up undermining created agency.” “Occasionalism,” JEE, 415-19.

Off stage, between 2006 and (roughly) 2020, Crisp trained several doctoral students with various levels of investment in Edwards scholarship. Most of them had a passing interest in Edwards.52Ross Hasting, Stephen Nichols, Joshua Farris, and Jordan Wessling are Crisp students who had, we might say, a brush with Edwards in the course of their careers, some contributing a chapter, others an article, and in two cases a monograph to the Crispian tradition. Colored by his interest in the Karl Barth, Ross Hastings extended Crisp’s analytic reading of Edwards into an extended retrieval project, focused on the doctrine of Theosis. Ross Hastings Jonathan Edwards and the Life of God: Toward an Evangelical Theology of Participation (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2015). Nichols, jumped streams, taking Crisp’s analytic intuitions into an extended study on Edwards’ exegesis of Scripture and the doctrine of salvation. Stephen R. C. Nichols, Jonathan Edwards’ Bible (Eugene: Wipf and Stock, 2013). Swept up into the novelties of Edwards’ idealism, Farris extended Crisp’s reading of Edwards into a contemporary analytic discussion of the imago dei. Joshua R. Farris, ‘Edwardsian Idealism, Imago Dei, and Contemporary Theology,” in S. Mark Hamilton and Joshua R. Farris, eds. Idealism and Christianity, Vol. 1: Christian Theology (New York: Bloomsbury), 83-106. Wessling fastened onto Edwards’ moral theology, but used Edwards’ divine self-glorification commitment in The End for which God Created the World as a foil for other schemes. Jordan Wessling, Love divine: A Systematic Account of God’s Love for Humanity (New York: Oxford University Press, 2020). Wessling’s argument is interestingly similar to Channing’s, two hundred years ago: “‘The glory of God,’ they say, ‘is our chief end;’ and this is accomplished as they suppose by taking all power from man and transferring all to his Maker. We have here an example of the injury done by imperfect apprehension, and a vague misty use of Scripture language. The ‘glory of God’ is undoubtedly to be our end… We do not honour him by breaking down the human soul, by connecting it with him only by a tie of slavish dependence. By making him the author of a mechanical universe, we ascribe to him a low kind of agency. It is his glory that he creates beings like himself, free beings, not slaves.” Channing, “Introductory Remarks,” 18-19. Crisp appears to agree: “The worry is that his understanding of the role creation plays makes of it merely a means to an end, namely, the greater glory of God. It is a strange doctrine that makes creatures merely instruments used to bring about some greater goal, rather than regarding them, in the final analysis, as ends in themselves.” JEE, 318. Few showed concern or interest in the negative entailments of Edwards’ occasionalism, continuous creationism, or panentheism. Only two students—Myself (Mark Hamilton) and Chris Woznicki—have consistently plied the Edwardsean trade. Hamilton has recently attempted to modify Edwards’ “flip book” picture of the world.53Hamilton, A Treatise on Jonathan Edwards, 27, 31, 34, 40. Dissenting from Crisp’s reading of Edwards’ idealism, Hamilton argues that Edwards’ commitment to immaterial realism accounts for his doctrine of continuous creation as well as the secondary causal activities attributed to human nature of Christ. Woznicki, by contrast, agrees with Crisp’s interpretation and has focused on defending it from Hamilton.54Christopher Woznicki, “The Metaphysics of Jonathan Edwards’ ‘Personal Narrative’: Continuous Creation, Personal Identity, and Spiritual Development,” Neue Zeitschrift Für Systematische Theologie Und Religionsphilosophie 61, no. 2 (May 28, 2019): 184–206, https://doi.org/10.1515/nzsth-2019-0010. What is interesting in Woznicki’s research is the appeal to the analytic “consensus” of Edwards’ flip book ontology to stave off Hamilton’s amendments. Hamilton, by contrast, recasts the flip book analogy altogether in terms of a film projector. Overall, however, there has been little dissent from within the camp.

2018—present: A Settled Consensus

In what might not be unjustly characterized as a passing of the torch, in 2018, Crisp co-authored Jonathan Edwards: An Introduction to His Thought with Kyle Strobel. As an introductory text, it will doubtless ensconce Crisp’s reading of Edwards’ occasionalism, continuous creation, and panentheism to another generation of students.55Edwards’ God being responsible for the authorship and agent of evil also continues on. JEIT, 113. This moment is important because it means the “Edwards of Philosophy” is transitioning outside analytic circles into settled theological readings. Occasionalism, continuous creationism, and panentheism are becoming the abnormal normal, so to speak, in reading Edwards. Strobel might object to this characterization, especially because his final chapter, “Becoming Edwardsean,” is an attempt to fix the seemingly “downright unhinged” parts of Edwards by simply amputating them.56JEIT, 198. Strobel claims eight times that Edwards has a “non-contrastive impulse” in his final chapter “Becoming Edwardsean.” JEIT, 205, 208, 208, 213, 215, 216, 217. But there are problems. He claims that “Edwards employs non-contrastive theological language, where God’s causation does not create a zero-sum game with creaturely causation, but his philosophical material undermines the ultimate meaningfulness of this language (and a zero-sum game emerges).” JEIT, 211. But Strobel also claims (following Kathryn Tanner) that occasionalism falls into a contrastive model of divine transcendence that renders reconciliation between human free will, divine agency, and evil impossible. Strobel would have been better served claiming something else. Namely, Edwards wants to retain classical doctrinal commitments, but due to his “anti-deistic impulse,” accidentally ends up in contrastive accounts of divine and human causation. It is not at all clear that Edwards has a “non-contrastive impulse” on Strobel and Crisp’s presentation. In recommending this move, he is repeating what Crisp and Cochran observed back in 2005.

III. The “Edwards of Faith” fused with the “Edwards of Philosophy”

What happens when the “Edwards of Philosophy” is let loose within the “Edwards of Faith” readership? This section explores the implications for such experimental fusion.

Carrick’s Conundrum

On the interpretation handed down by Helm, Crisp, and now Strobel, Edwards’ Freedom of the Will and Original Sin are incoherent.57 Shockingly, Carrick is not the first scholar to attempt to drive a major wedge between Freedom of the Will and Original Sin. Amy Plantinga Pauw agrees with Michael McClymond that last six hundred pages of Edwards’ published writings are “not nearly as central to Edwards’ lifelong intellectual concerns as is commonly thought.” McClymond uses three pieces of evidence to make this case. First, he claims that Freedom of the Will and Original Sin are “much like the revival and ecclesiastical treatises, these were occasional writings, even though grandly conceived and executed… that ‘Arminianism’ compelled him to write.” Second, McClymond cites the greater preponderance of Miscellanies pertaining to The End over and against those pertaining to Freedom of the Will. Finally, he concludes: “Yet even if I am wrong in this judgment, it is clear that neither Freedom of the Will nor Original Sin had much relation to the vast magnum opus that Edwards planned to write but died without commencing.” Pauw, The Supreme Harmony of All: The Trinitarian Theology of Jonathan Edwards (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 7n.24 citing McClymond, Encounters with God: An Approach to the Theology of Jonathan Edwards, Religion in America Series (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), 6n.11. This is a bizarre case to make by McClymond and Pauw. Contra the first point, Edwards spent approximately a decade reading, notetaking, assembling, and writing Freedom of the Will and Original Sin. He did not just start them once he had spare time in Stockbridge. Not only that, but they are also the two projects he prioritized by writing first, while at the same time collecting materials for six other book projects. Contra the second point, if one is just counting Miscellanies titles, McClymond’s evidence would prima facie appear true. However, this elides the fact that Edwards had several notebooks – a minimum of eight for Freedom of the Will and three for Original Sin – that corroborate the importance of these books for Edwards. Finally, the suggestion that Freedom of the Will and Original Sin did not have a substantial relationship to Edwards’ later volumes says enough on its own and needs no rebuttal. For a vision of Edwards’ works where they all hang tightly together, see C. Layne Hancock, “Saving Jonathan Edwards’ Ethics from Voluntarism” (PhD dissertation, South Bend, IN, University of Notre Dame, 2024), chap. 2, https://curate.nd.edu/articles/dataset/Saving_Jonathan_Edwards_Ethics_from_Voluntarism/25527391. Worse, the entailments of their interpretation force readers to choose between Edwards being a liar or his being wildly ignorant. We will come to this dilemma after we unpack the purported incoherence between Edwards’ two treatises.

If occasionalism is true and God is the one true cause, then questions arise over secondary (or creaturely) causation. Do we have any causal heft? The answer from Crisp and Strobel is unclear. Sometimes they offer a weaker claim: Edwards’ accidentally or unintentionally “undermines creaturely causation.”58JEIT, 206. Or Edwards “takes away the ultimate meaningfulness” of secondary causes. JEIT, 210. A slightly stronger claim like “Edwards can give an account of secondary causality… [but] it does not end up doing the work it was meant to do, which was to carve out adequate space for creaturely causation” and “Edwards flattens out the [Reformed tradition’s] schema of secondary causation also appear. JEIT, 206n.21; 209. Other times they offer a much stronger claim: Edwards cannot (i.e., is not logically entitled to) talk about secondary causation.59Crisp: “In the final analysis, Edwards’ occasionalism cannot preserve the distinction between divine causation and divine moral action.” JEE, 418. Strobel: “Because of the philosophical system Edwards employs, he can talk about creaturely freedom and causation within each world-stage, but as we have seen there is no actual creaturely causation available-nothing obtains for long enough to cause anything to happen. Edwards ‘talks in the vulgar,’ as it were, making it sound as if his view accords with how we tend to view the world; but once his philosophical positions are clarified, a much different picture appears.” JEIT 211. More recently, Strobel: “Now God is recreating the world every moment. So, what we have is a flip book account of creation, or those old movie reels where really nothing’s moving on the screen, they’re all stills, but if you make them move fast enough, it appears that there is motion… The problem is there’s no actual causality happening here because it’s a still frame. But Edwards is worried that if we don’t have continuous creation that one of two things will occur. Either we’re going to have a creaturely freedom that pushes God outside of creation in a deistic frame, or we are going to lose any account of creaturely freedom whatsoever… Edwards gives us an account of continuous creation, idealism, and occasionalism to try and salvage creaturely freedom and action. I want to say that’s a bad way to do that… there’s going to be all sorts of problems. The question is why? … He was handed determinism, and he really wants creaturely freedom and causation. As an Edwardsean I want to say there is a better way to do that. To say what Edwards clearly wanted to say: God does all, God is fully actual in his primary causality and I do all, I have real creaturely freedom and causation from within God’s actuality,” Strobel-Smith, “Jonathan Edwards (If You Can Keep Him),” 19:20. The strongest claim is that “Edwards thinks he can, in fact, talk about a kind of secondary causality, despite the fact that there is no actual creaturely causality.”60JEIT, 210. This quote reads as if Edwards is asserting A and ~A. All of this is quite confusing. We think what Crisp and Strobel mean to say is that Edwards affirms that there are secondary entities (i.e., creatures) who lack the power of efficient causation because they are stuck in the “flip book” of continuous creation.61JEIT, 207, 210. Secondary entities do not, metaphysically speaking, have causal powers—only God does. When Edwards speaks of “his going to Boston” or of “Hopkins coming to visit Stockbridge” or “deviant teenagers passing around a midwifery book,” these are all “vulgar” ways of speaking about secondary entities that appear to have causal powers and interaction in the world, despite these appearances being metaphysically false. Therefore, Edwards logically cannot appeal to secondary causes in his system.62Again, the ambiguity over whether Edwards endorses secondary causation or occasionalism is not new, but it is carried out as if it were new. See the dispute between Frank Hughes Foster, who affirms the former, and Paul Ramsey, who affirms the latter in WJE 1.36n.5; Frank Hugh Foster, A Genetic History of New England Theology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1907). Ramsey thinks the whole issue is unambiguous. Edwards was influenced by Hume’s skepticism about causation and became an occasionalist. Foster seems ambiguity. First, he claims that Edwards, due to Malebranche’s influence, is unclear on whether the will is an efficient or occasional cause; “At the very foundation of the edifice he was about to rear [in Freedom of Will], and destined to make its whole structure insecure to the highest pinnacle” (64). After surveying the relevant texts, Foster concludes that secondary causes are real in Edwards, notwithstanding the interpretations of Jonathan Edwards Jr. and Stephen West, whom he classifies as “partisan interpreters” committed to occasionalism (71n.17, 229-245).

This occasionalist/continuous creationist reading immediately prompts the question: what on earth is Edwards doing for three hundred and five pages talking about motives, volitions, moral ability, human agency, liberty of indifference, obligations, commands, praise, blame, virtue, vice, acts, habits, and denying that God is the author of sin in Freedom of the Will?63WJE 1.397-412; Freedom of the Will IV.9 Crisp says it “is very difficult to see how one can salvage a robust account of creaturely moral responsibility from [continuous creationism],” which, given the lengthy nature of Freedom of the Will, is quite the understatement!64Strobel and Crisp, JEIT, 120. Readers need some explanation for why Edwards toiled on about creaturely causation for almost a decade.65The notebooks that eventually funded Freedom of the Will started c.1739-1743. Crisp claims that Edwards “says far less about the nature of causation” when compared to his discussion of occasionalism and continuous creationism in Original Sin IV.3. He cites the infamous two-page definition of “cause” in Freedom of the Will as if it is the only place where Edwards discusses causation.66Crisp, JEMS, 130-31. This claim is just begging the question. Edwards is wrestling with causal theories and Newtonianism throughout his entire life. Although it is true that it is spread across various notebooks and miscellanies – he certainly doesn’t make it easy on scholars – but it doesn’t mean he says “far less” about causation. Crisp typically cites Miscellany 267 and WJE 4.316 (a definition of causation in the context of the exceptional case of the miraculous, not the mundane by the way) to supplement picking out “occasion” here in WJE 1.181. After reading through all of Edwards’ Miscellanies, philosophical writings, theological treatises, and some of his sermons chronologically with an eye towards Edwards’ development, by my (Layne) count, there are at least 72 places in Edwards’ corpus that have a direct bearing on his causal concepts and continuous creation – not including Original Sin. While Original Sin is among the latest documents, there are reasons internal to that text that push against an occasionalist reading that we look forward to addressing in future publications. Yes, the word “occasion” appears in Edwards’ definition of “cause” here—but this is one word in a 530-word definition that includes other loaded metaphysical words like “ground,” “reason,” “moral,” “natural,” “positive,” “negative,” etc.67WJE 1.180-81. Helm, Crisp, and Strobel failed to understand why Edwards is so verbose in this definition and instead fixated on one word. In the scholastic tradition, Plato and Aristotle’s αἰτία was translated into the Latin causa with a far greater range of meaning than the English word “cause” – classically encompassing formal, final, material, and efficient explanations. We read Edwards’ verbosity in WJE 1.180-81 as an attempt to retain the broad scope of causa as levels of explanation, not reducing all explanations down into an occasional cause. See Gregory Vlastos, “Reasons and Causes in the Phaedo,” The Philosophical Review 78, no. 3 (July 1969): 291, https://doi.org/10.2307/2183829. Furthermore, merely citing Edwards’ statement—“I sometimes use the word ‘effect’ for the consequence of another thing, which is perhaps rather an occasion than a cause, most properly speaking”—does not explain how readers should reconcile the occasionalism of Original Sin with the rest of Freedom of the Will.68WJE 1.181. Emphasis ours. If anything, this meager “perhaps” connection to the notorious closing ten pages of Original Sin calls out for more explanation, not elision.69It would be silly to pit word-counts or pages against Edwards’ works. Inevitably, later texts will have a kind of priority, even if they come in smaller sections. Perhaps Helm, Crisp, and Strobel think that, since Original Sin is later (1758) than Freedom of the Will (1754), that Edwards changed his mind on causation or made his latent commitments more explicit in the former. But if they think this, they have never said so. And so, on the “Edwards of Philosophy,” we have no story to tell about how to harmonize the agency of Freedom of the Will with the non-agency of Original Sin.

Let us name the apparent incoherence between the occasionalism of Original Sin and the human agency of Freedom of the Will “Carrick’s Conundrum.”70Carrick, JEIG, 51–52 and 47–49. In [Freedom of the Will], Edwards insists upon the temporal causation of events; in the [Original Sin], he insists upon a doctrine of temporal parts. In the former treatise, Edwards insists upon the effect of “antecedent bias” [of the will]; in the latter, he denies the effect of “antecedent existence.” The name comes from Carrick’s Jonathan Edwards and the Immediacy of God (2020). As a fusion of the “Edwards of Faith” and the “Edwards of Philosophy,” it brings the tensions to light in a way that is absent in recent treatments of Edwards. We read Carrick’s book as a kind of logical conclusion—the dead end—of the Helm-Crisp-Strobel interpretation of Edwards.71Carrick dedicates his book to “Paul Helm: mentor and friend,” and it was Helm “who first suggested [to Carrick] that the theme of the immediacy of God in the thought of Jonathan Edwards might prove to be a fruitful and rewarding study.” JEIG, v. Carrick also implies that Helm has been “helpful as a mentor” in “the year of writing” this book. JEIG, ix. Obviously readers should not hold Helm responsible for Carrick’s Edwards, but we were unable to find anything but a faithful reproduction of Helm and Crisp’s Edwards throughout the book. Carrick could be referring to Helm’s discussion of divine immediacy in Edwards in “Epistemology,” in OXJE, 105–6. (This section is not a review of Carrick’s book—for many reasons.72The book is not to be recommended to anyone wanting to learn about the historical Edwards. It is filled with mistaken citations (e.g., WJE 6 instead of WJE 3. JEIG, 29; “Miscellany” instead of “Notebooks on Efficacious Grace.” JEIG, 71–74; citing the editors of The Search After Truth instead of the author, Nicholas Malebranche. JEIG, 33–34). Carrick also makes several basic category mistakes. For example, in his Conclusion, he faults Edwards for believing in “continuous creation” and not “continuous revelation” – as if the concepts shared anything besides the modifier. JEIG 134. Carrick suggests that John Taylor, Samuel Clarke, and George Turnbull were all deists, despite the fact Edwards never labels them so and that each of them opposed deism in their own writings. JEIG 69–75. And, almost out of nowhere, claims that Arminianism is a slippery slope to Pelagianism which is a slippery slope to Unitarianism, concluding with a rant against libertarianism despite the fact Carrick cannot bring himself to endorse Edwards’ occasionalist alternative. JEIG, 78–81.)

Carrick’s thesis is that the immediacy of God is the key theme that runs through all of Edwards’ disparate writings.73Carrick, JEIG, 136. Think of “divine immediacy” as a kind of public affairs re-branding; an attempt to make occasionalism, continuous creationism, and panentheism more palatable. Carrick is an author deeply sympathetic to the “Edwards of Faith,” having previously published a book commending Edwards’ preaching for Banner of Truth.74 John Carrick, The Preaching of Jonathan Edwards (Edinburgh, Scotland: Banner of Truth Trust, 2008). But in this book, Carrick struggles to reconcile the Northampton Sage he admires with the “Edwards of Philosophy” he has inherited from the writings of Helm, Crisp, and Strobel. In fact, Edwards and the Immediacy of God follows Crisp and Helm so closely that Carrick reproduces large sections of their arguments into full-page block quotes.75The follow correlations draw on a wide range of the “Edwards of Philosophy” literature. Carrick’s abstract of the book (JEIG, 5) and his “Continuous Creation” section (JEIG, 23-27) work from Paul Helm, “Jonathan Edwards on Original Sin,” in Faith and Understanding, Reason & Religion (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997), 152–76; Paul Helm, “A Forensic Dilemma: John Locke and Jonathan Edwards on Personal Identity,” in JEPT, 45–60. Carrick’s “The Doctrine of Temporal Parts” and “Sang Hyun Lee” sections (JEIG 30-33) are influenced by Paul Helm, “Jonathan Edwards and the Doctrine of Temporal Parts,” Archiv Für Geschichte Der Philosophie 61, no. 1 (1979), https://doi.org/10.1515/agph.1979.61.1.37; Oliver D. Crisp, “Temporal Parts and Imputed Sin,” in JEMS, 96–112; Crisp, JEGC, 14-36. The same is true of Carrick’s “The Laws of Nature” (JEIG, 36-38 cf. JEGC, 30, JEAT, 166). Carrick’s “The Question of Panentheism” (JEIG, 40–44) sources Oliver D. Crisp, “Jonathan Edwards’ Panentheism,” in Jonathan Edwards as Contemporary: Essays in Honor of Sang Lee, ed. Don Schweitzer (New York: Peter Lang, 2010), 107–26; JEGC chap. 7 Panentheism. Finally, Carrick’s “Is Edwards’ God the Author of Sin?” (JEIG 57-62) working from Crisp’s “The Authorship of Sin,” in JEMS, 54–78, esp. 64, 130–33. The most significant objection that Helm, Crisp, and Strobel could put forward against Carrick’s aggregation of their reading is that they are strung together in a way that doesn’t offer a charitable reading of Edwards’ motivations. This is true and to their credit, Helm, Crisp, and Strobel typically seek to explain why Edwards became stranded in these ridiculous positions. Still, insofar Carrick’s images and concepts are entirely from the “Edwards of Philosophy,” the problems remain, and they are not solved by charitable readings alone. Consider Strobel’s latest approach to motivate charitable readings: “Edwards isn’t a determinist by choice… In a post-Newtonain cosmology, Edwards is handed a mechanistic universe. He’s handed a deterministic framework and Edwards is desperately trying to figure out how to salvage creaturely causality within this framework… My read on Edwards is that he turns to radical philosophical notions to try to be classical within a post-Newtonian cosmology that in his estimation seems unavailable… In a mechanized universe, you have two options as a Christian. Either God really does nothing, and creation is fully function on its own, natural causality is the only kind. This is a Deistic framing… Or you go totally the other direction and God does everything. What is this [earthly] machine? It’s God. Edwards as a Reformed Christian is going to choose the latter option. This is panentheism. Although this is anachronistic framing. Edwards wasn’t looking at several options and saying, ‘I’m going to be a panentheist!’ … When Edwards tries to give an account of this, keeping in mind that he’s handed a mechanized universe, he tries to figure out how to allow room for creaturely freedom, creaturely causality, and say classical things.” Strobel-Smith, “Jonathan Edwards (If You Can Keep Him),” 13:00. We will show why this defense doesn’t work very well in the eternal genders analogy later in this article.

To his credit, Carrick recognizes the conundrum that Helm, Crisp, and Strobel have mostly passed by:

Another strand in the potential resolution of [the absence the continuous creationism of Original Sin in Freedom of the Will] is the possibility that, at this point in these two works, Edwards is dealing with matters at two different levels. It is quite possible that Edwards is making an implicit distinction here between… speaking in “a strict and philosophical sense” and speaking “in a loose and popular sense.” … According to this view, Edwards can be construed as “thinking with the learned” and speaking in “a strict and philosophical sense” in his continuous creation-cum-occasionalism doctrine in Original Sin, and he can be construed as “speaking with the vulgar” and speaking in “a loose and popular sense” in his determinism in Freedom of the Will—in the former treatise he is utilizing the language of the philosopher and in the latter the language of the shop.76Carrick, JEIG, 64.

What, exactly, does loose/strict sense distinction mean? Carrick continues, claiming that,

according to this hypothesis, the seemingly irreconcilable problem is, in fact, fairly easily solved: the occasionalism of Original Sin emerges in the course of his metaphysical treatment of issues, while the determinism of Freedom of the Will emerges in the course of his non-theoretical treatment of issues.77Carrick, JEIG, 64.

Carrick seems to be building on Crisp and Helm’s scattered remarks on the possibility that Edwards borrowed George Berkeley’s vulgar/strict sense distinction.78Again Carrick seems to have been put onto this Edwards connection to Berkeley and Butler through Helm, who wrote about it in passing. Carrick, 64, 5; Helm, OXJE, 105; JEIT 67-74. His metaphor is that Freedom of the Will is “shop-talk” while Original Sin is “metaphysics-talk.” How exactly this solves Carrick’s conundrum is unclear. Are the “learned” just able to handle the controversial truth that they have no agency, while the plebians cannot? It seems to name the problem rather than solve it.

Carrick sometimes puts the conundrum a bit too complex. The contradiction is quite simple:

- In Freedom of the Will, it appears that creatures have some kind of agency.

- In Original Sin, it appears creatures have no agency.

This is Carrick’s Conundrum. What can be said in response?

There are so many problems with Carrick’s attempted solution that one can understand why perhaps Helm, Crisp, and Strobel avoided opening this pandora’s box. Let’s start with the four most pressing problems with Carrick’s solution:

- Edwards says the exact opposite of Carrick’s metaphysics-talk/shop-talk division in several notes to himself on “PROPOSALS” for Original Sin. This book is meant for clergy and the laity who are being misled by dissenting pastor John Taylor, whereas Nature of True Virtue and “The Mind” are intended for a “learned” audience, taking on university professors and academics.79WJEO 34 “Arnauld ed.” 5-6. Edwards writes these back-to-back: “PROPOSALS. The discourse on original sin will be more adapted to the understandings of such as have not been conversant in the writings of the modern reasoners on the nature of virtue and God’s end in creating of the world, who have opposed the opinion of such as used to be esteemed orthodox divines [i.e., the Westminster Assembly] on these heads; and may perhaps be more agreeable to the taste of such as have no disposition or leisure to be at the trouble of acquainting themselves with those controversies. PROPOSALS. There may be many that may be willing to read a defense of original sin that are not conversant in late controversies about God’s end in creating the world, nor the new and most fashionable notions about the nature of virtue, and have no disposition to look into those things. To such as these, some things in these two first discourses may not be so intelligible.” For an aggregation of these statements and background, see Hancock, “SJEE,” chap. 2.2.

- Freedom of the Will is replete with metaphysical discussion, so much so that Edwards dedicates his final section (IV.13) to defending the importance of metaphysics.80WJE 1.423–29. So Carrick’s solution does not accurately describe this work either.